In the world there exists a country where I will not be out of place.

Yuri Kolker, Leningrad, 1983

Lenin viewed the Zionist movement as bourgeois and reactionary, claiming that it distracted Jewish workers from the more important goal of class struggle. Thus, it is not surprising that soon after the October Revolution, the Soviet authorities began a struggle against the Zionists, which became fiercer over the years.

Although it was sometimes allowed out of pragmatic considerations, emigration from the USSR was never free. According to incomplete data, before the Second World War, approximately 70,000 Jews emigrated. Half of them made their way to Mandate Palestine.

When the Soviet regime annexed territories of the Baltic States, Poland and Romania between 1939 and 1940, it persecuted thousands of activists in the process of repressing the Zionist movement there. Immediately after the war, Polish Jewish refugees in the Soviet Union, along with some Jews who had been citizens of Romania, were repatriated and then made aliya. Many of those who were not allowed to emigrate attempted to cross the Soviet border illegally, but were arrested and sentenced to long jail terms.

As for the long-time Soviet Jews who lived in the territories that had been part of the USSR before 1939, their loyalty was called into question during the war years and afterwards. Anti-Semitism, which had been dormant in the Soviet Union, emerged in the occupied territories, in the rear and at the front. It began to be felt also in Soviet personnel policy - the government refused to restore Jews to the, often high, positions they had held before the war. After the liberation of territories that had been occupied by the Nazis, the Soviet leadership obstructed the return of the Jews, especially in Ukraine. At the same time, official propaganda refused to acknowledge that the Jews had been the main target of the Nazis' racist policy.

The Holocaust and anti-Semitism increased Jewish sentiments not only among traditional Jews but also among their more assimilated, sovietized cousins – who had believed in the friendship of nations and were largely indifferent to their own national origin.

Various Zionist groups were established. An underground organization called Eynikeyt (Yiddish for "unity") operated in 1945-46 in the city of Zhmerinka, in the province of Vinnitsa, distributing handwritten leaflets with a Zionist message. Members of the group were arrested and sentenced to long prison terms. However, their activity had not been in vain. In 1948, Jews from Zhmerinka dared to send a collective letter to Pravda, requesting that the Soviet authorities allow them to leave for Israel.

Zionist sentiments among Soviet Jews were also encouraged by actions of the Soviet Union. At the United Nations the USSR strongly supported the establishment of two independent states in the Middle East – one for Arabs and one for Jews. The USSR was also the first country to establish diplomatic relations with Israel.

The establishment of the Jewish state aroused a storm of enthusiasm among Soviet Jews. Jewish war veterans even appealed to the government and to the Jewish Anti-fascist Committee for permission to go as volunteers to defend the newborn Jewish state. There were also efforts to collect money to aid Israel, where many Jews believed they would be allowed to settle.

However, the government had different plans. On September 21, 1948, Pravda published an article by the well-known writer, Ilya Ehrenburg. Ehrenburg expressed an unambiguous warning to Soviet Jews that this new state should not be considered to have any relevance for them.

Soon after the end of the war an unprecedented broad and severe anti-Semitic campaign was launched. The murder of the famous Jewish actor, director and public figure, Solomon Mikhoels (1948), the liquidation of the Jewish Anti-fascist Committee, the arrests and consequent trial and execution (1952) of its members, a ban on Yiddish culture, an extensive propaganda campaign against “rootless cosmopolitans" (i.e., Jews) (1949), and the secret police-fabricated "Doctors’ Plot" (1953) were major events during these "Black Years" of Soviet Jewry.

The persecution of Jews from 1948 to 1953 created an impassable chasm between them and the state. In response, Zionist groups and circles were formed. In Moscow Vitaly Svechinsky, Mikhail Margulis and Roman Brakhman were among the activists – and there was also a group of Hebrew writers that included Moshe Hiyog and Zvi Preigerson. In Odessa the leaders were Yosif Khorol and Alexei Khodorovsky, in Kharkov a leader was Yefim Spivakovsky. However, the secret police discovered their activities and they were sent to the GULAG for 10 to 25 years.

The post-Stalin "Thaw" was marked, among other things, by the first trickles of Jewish emigration to Israel: 53 emigrants in 1954, 106 in 1955, and 753 in 1956. Those who left were mostly older people, who were allowed to emigrate under the slogan of family unification. After the 20th Congress of the Communist Party of the USSR, in 1956, Zionists were among those released from prison camps. The Yiddish writers who had been executed were posthumously rehabilitated. In 1957, the Moscow Choral Synagogue was allowed to publish a prayer book and to open a small yeshiva. Another indication of the "Thaw" was the decline – but not the disappearance – of anti-Semitism in employment.

The presence of a large Israeli delegation at the Festival of Young People and Students in Moscow, in 1957, created a great stir among Jews. Many Soviet Jews made contact with the Israelis, speaking about their desire to emigrate, and requesting information about Israel and study aids for learning Hebrew. Soon, however, it became clear that the Soviet regime did not forgive unsanctioned meetings of its citizens with foreigners, especially citizens of Israel. Dozens of Zionists paid with the loss of their freedom for contacts with the Israeli delegation or staff of the Israeli embassy or for distributing information about the Jewish state. These victims included the Podolsky family, Tina Brodetsky, David Havkin and Naum Kaganov in Moscow, Baruch Vaisman, Meir Dreiznin, Girsh Remenik and Yaakov Friedman in Kiev, Yosif Kamen in Dnepropetrovsk, Anatoly Rubin in Minsk, and Gedaliya Pechersky, Yevsei Dynkin and Natan Tsirulnikov in Leningrad.

The synagogue became a meeting place for nationally conscious Jews. In 1959, on the holiday of Simhat Torah, 30,000 Jews, mainly young people, gathered around the Moscow synagogue. People hailed the performances of Israeli athletes, musicians, singers and film figures. Among the especially popular Jewish singers were Nechama Lifshits, Mikhail Alexandrovich, Sidi Tal, Anna Guzik and Emil Gorovits.

Arrests of activists between 1957 and 1962 did not succeed in destroying the Zionist movement. In the second half of the 1950s, Jewish samizdat (underground publications) began to appear. It was difficult and dangerous to make copies of samizdat material since access to copy machines was carefully guarded by the State. In the 1960s one of the most important distributors of samizdat and information from Israel was Meir Gelfond, a member of the Zhmerinka Zionist group who moved to Moscow. Among the important "publications" of samizdat were poems by Bialik, essays by Jabotinsky and historical works by Dubnov, and the samizdat Russian translations of Howard Fast’s My Glorious Brothers and Leon Uris’s Exodus. The latter became a kind of "Bible" for a whole generation of Zionists in the USSR.

In Riga Yosif Shneider, Dov Shperling, Yosif Yankelevich, Yosif Khoral, Lea and Boris Slovin and Gesia Kamaisky undertook the copying and distribution of samizdat in the Baltics, Moscow, Leningrad and, even, Siberia. Mark Brudny, Marek Moizes and the Goltsmans were active in Vilnius, and Venyamin Zukerman in Tomsk. Volt and Esther Lomovsky and Talmon Pachevsky were organizers of Zionist activity in Novosibirsk.

Memorial ceremonies at locations of mass execution of Jews during the Second World War served as another important means of strengthening national consciousness and Zionism. These meetings took place at such sites as Rumboli near Riga, Babi Yar in Kiev, Ponary in Vilnius, Yama – where the Minsk Ghetto had been located – and Drobnitsky Yar near Kharkov. Participants called for memorials to be established that would indicate clearly that the victims were Jews, and not simply, as the Soviets had previously defined them, “peaceful Soviet citizens.”

Israel’s outstanding victory over the united Arab armies in the Six Day War not only instilled a feeling of national pride in the hearts of Soviet Jews but also increased their alienation from the Soviet state, the ally of Israel’s enemies. After 1967, the “Soviet citizens of Jewish nationality” were transformed from Jews of Silence, as in the title of Elie Wiesel’s book, to Jews of Hope, as the British historian Martin Gilbert referred to them in his book of 1984. The number of those who identified with the Jewish state and engaged in the struggle for repatriation increased.

On June 13, 1967, Moscow student Yaakov Kazakov publicly renounced his Soviet citizenship and demanded to be allowed to go to Israel. In an appeal addressed to the deputies of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR Kazakov wrote:

”I do not wish to be a citizen of a country where Jews are subject to forced assimilation. My people is deprived of its national features and its cultural values . . .

I do not wish to be a co-participant in the destruction of the State of Israel . . .”

Kazakov received an exit permit in February 1969.

In Leningrad, in 1966, underground Zionist youth organizations headed by David Chernoglaz and Hillel Butman combined to form a single organization that had a platform of its own, a charter, a network of ulpanim to teach Hebrew, and connections with Zionist groups in other cities. In addition to Chernoglaz and Butman, the organizational committee included Aron Shpilberg, Solomon Dreizner, Vladimir Mogilever, Lev Yagman, Lassal Kaminsky, Anatoly Goldfeld and Lev Korenblit.

In contrast to Leningrad, in Moscow initiatives usually came not from the youth but from veteran Zionists, who had spent time in prison camps or in jail. Among these were Meir Gelfond, Vitaly Svetchinsky, David Khavkin and Israel Mints, whose group was joined by Yosif Begun and Vladimir Slepak, of the younger generation. Moscow Zionists had ties with the dissident movement, foreign journalists and diplomats.

By the fall of 1969, at the initiative of Aron Shpilberg, who had come from Leningrad, a Zionist youth organization was established in Riga that included Yosif Mendelevich, Eliyahu Valk, Yaakov Tseitlin, Moshe Druk and others. The total membership of the Riga groups exceeded 150. The movement in Riga had support among broad circles in the local Jewish and even non-Jewish communities. In Odessa, in the late 1960s, there were two Zionist groups. The one headed by Abraham Shifrin included Raiza Palatnik and Yishayahu Averbuch. The second was headed by Moshe Melkher. Yishayahu Averbuch, who had begun as a dissident, was in contact with Boris Maftzer and Ruth Alexandrovich in Riga, who were responsible for bringing samizdat to Odessa. In Kiev, Boris Kochubievsky wrote and circulated his samizdat article, “Why I am a Zionist." For this, he was put on trial in 1968.

The secret Soviet quotas that limited the admission of young Jewish people to prestigious institutes of higher education had an unintended effect: they spread Zionist ideas. This occurred when young Jews who were rejected for studies in the major cities had to study in the provinces and brought sparks of Zionism with them. Thus, the Zionist movement reached Ryazan, Tomsk, Novosibirsk and Irkutsk. In Ryazan, in 1970, six Jewish activists, including Yury Vudka, were put on trial on the usual charge of “anti-Soviet propaganda.”

In the late 1960s, Jews began to address collective letters and appeals to Soviet and international organizations, demanding the right to emigrate, as stipulated in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. On August 6, 1969, 18 heads of families of Georgian Jews sent a letter to the United Nations that included the following words: “We believe that our prayers have reached God. We know that our appeals will reach people because we are not asking a great deal. Let us go to the land of our ancestors.” Another letter, to Secretary General of the United Nations U Thant, was signed by 531 Georgian Jews. It ended with the words “Israel or death.”

On March 4, 1970, within the framework of an anti-Israel propaganda campaign, a national televised press conference from Moscow featured Soviet "court Jews." Moscow Zionists responded with an open statement that was signed by 40 refuseniks. Between 1968 and 1978 Soviet Jews sent more than 2,300 letters (some collective and some individual) addressed to the Soviet authorities and Western public opinion.

In Moscow, in August 1969, Soviet Zionists established an underground national All-Union Coordinating Committee. Initially, the Committee had representatives from Moscow (Gelfond, Svechinsky and Khavkin), Leningrad (Mogilever and Dreizner), Riga (Valk and Maftser), Kharkov (Y. Spivakovsky), Kiev (Anatoly Gerenrot) and Tbilisi (Gershon Tsitsuashvili). The Committee decided to launch a publication, Iton [Hebrew for "newspaper"] that would serve as a mouthpiece for the movement and would be published in Riga.

In 1969, the number of exit permits granted in response to invitations from Israel reached a peak of almost 3,000, but that was still far fewer than those requested them. Some activists concluded that the only way out of this impasse was a desperate demonstrative act. The one chosen was an attempt to hijack a small airplane and to fly it to Sweden.

The Committee of the Leningrad Zionist organization, after hesitation and consultation with the Israeli government, rejected the plan as unrealistic and posing a threat to the movement itself. Nevertheless, the operation, under the code name "Operation Wedding," was planned and began to be implemented by Riga and Leningrad activists headed by ex-political prisoner Edward Kuznetsov and former military pilot Mark Dymshits.

On the morning of June 15, 1970, all the participants were arrested by the secret police at Leningrad's Smolny Airport and in Priozersk, where four more Zionists were supposed to board the plane. The same morning, eight people who were not involved in the operation were arrested in Leningrad. Further arrests followed, resulting in a total of 34 defendants being put on trial in Leningrad, Riga and Kishinev. The sentences meted out to the hijackers at the first Leningrad trial, the so-called “Airplane Trial,” in December 1970, were unusually severe, especially since the hijacking was aborted and no one was hurt. Dymshits and Kuznetsov were sentenced to be executed; Kuznetsov's wife Silva Zalmanson, Yosif Mendelevich, Anatoly Altman, Arie Khnokh and others were sentenced to between 10 and 15 years of "corrective labor." Silva's brother Wulf Zalmanson was sentenced by a military tribunal to 10 years. Only international protests led to the commutation of the death sentences to terms of 15 years.

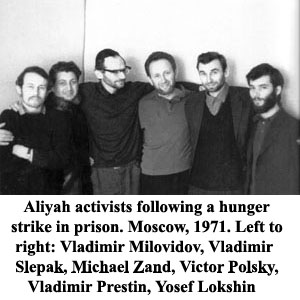

There was a second Leningrad trial in May 1971, and other trials in Riga, Kishinev, Sverdlovsk, Odessa, Samarkand and Lutsk, at which dozens of Zionists who had nothing to do with the hijacking were found guilty. The longest sentence – 10 years – was given to Hillel Butman who, with Dymshits, had initially proposed the idea of "Operation Wedding."

Those sent to jail became referred to as "Prisoners of Zion." Since the Soviet legal code did not stipulate any punishment for “Zionist activity,” Zionists were usually accused of involvement in "anti-Soviet agitation and propaganda (like, for instance, Yosif Begun) ," slandering the Soviet system (Vladimir Lifshits), or even espionage (Anatoly Sharansky). On other occasions, Jewish activists were arrested on fabricated charges involving criminal activity – for example, possession of narcotics or weapons (Alexander Kholmyansky, Alexei Magarik), or malicious hooliganism (Vladimir Kislik). Sometimes instead of being persecuted judicially, Zionists were incarcerated in mental institutions, like other dissidents (Nadezhda Fradkova).

The state security services sought to use the hijacking attempt to put an end to the Jewish movement. However, the result turned out to be quite the opposite: the movement became more active and emerged from the underground. The struggle for aliya became an open one.

Soviet Jews increasingly took part in public protests. On February 24, 1971, a large group of Jews from several cities held a demonstration in the reception room of the presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR – basically seeking permission to emigrate to Israel for themselves and official recognition of Soviet Jews’ right to repatriation, in general. This was followed by similar actions of Jews from Lithuania and Georgia at the Moscow Central Telegraph Office and of Jews from Kiev at Babi Yar. Refuseniks from Belorussia held a strike at the Ministry of Internal Affairs, and Georgian Jews staged a hunger strike.

While some of these demonstrations attained their goals, with the participants receiving exit visas, others ended with their arrests. On June 1, 1978, Moscow activist Ida Nudel hung a placard from her balcony that said “KGB, give me a visa to Israel.” For this she was sentenced to four years of internal exile on the charge of malicious hooliganism.

Reacting to increased Western support for the struggle of Soviet Jews and hoping that the Zionist movement would be weakened if "troublemakers" were allowed to leave, the Soviet government sharply increased the number of exit permissions. In 1971, 12,900 Jews left and in 1972 – 31,900. Their exodus involved a long bureaucratic process, severe humiliation, their condemnation by colleagues at work as traitors for leaving their homeland, and also the necessity of giving up their Soviet citizenship. In 1972, a law was passed requiring the departing Jews to pay a very high sum to repay the Soviet Union for the education they had received there. However, the government had to backtrack when the American Congress adopted the Jackson-Vanik Amendment that linked the provision of “most-favored nation” status for trade with the United States to Soviet permission for emigration.

During the wave of repatriation from 1969 to 1971, a majority of the veterans and leaders of the Zionist movement left the USSR. Thereafter, the struggle of Soviet Jews to emigrate was led by a new group, the scientific-technological intelligentsia of Moscow, like Alexander Voronel, Mark Azbel, Victor Polsky, Vladimir Prestin, Pavel Abramovich, Yosif Begun and Dina Beilin.

In Minsk the struggle for emigration to Israel included three war heroes who were retired colonels: Lev Ovsishcher, Naum Olshansky and Yefim Davidovich. Israel Rashal, also from Minsk, composed the song "Kakhol v'lavan," which became a kind of hymn of Soviet Zionists.

In Sverdlovsk, at the beginning of 1970s, Valery Kukui, Yuly Kosharovsky and Vladimir Markman were local Zionist leaders. Kukui and Markman were arrested and sentenced to three years’ imprisonment for “slandering” the Soviet regime. In Novosibirsk the struggle for emigration centered around the figure of the retired colonel of medical services, Isaak Poltinnikov. In the same city Felix Kochubievsky founded an association for friendship between the Soviet and Israeli peoples. For this Kochubievsky was arrested in 1981.

Among the leaders of the movement in Kiev were Vladimir Kislik, Alexander Tsatskes, Moshe Leonardes and Alexander Mizrokhin; leading activists in Tbilisi were the brothers, Grigory and Izya Goldstein.

Among the Soviet Jews who became refuseniks were a number of scientists who had formerly been connected to the military industry. After they requested to emigrate, these scientists with doctorates or candidate of science degrees were often expelled from their laboratories and institutions. In order not to fall behind scientific developments, they decided to conduct scientific seminars in their own apartments. The first such seminar was organized in 1971 at the home of Moscow professor of cybernetics Alexander Lerner. Scientific seminars in Moscow began to be held weekly, starting in 1973. Among the participants were Mark Azbel, Alexander Voronel, Viktor and Irina Brailovsky, Alexander Yoffe, Moisei Giterman and Vladislav Dashevsky. A number of foreign scientists, including some Nobel Prize winners, participated. Most of the papers or lectures dealt with physics or mathematics, but some discussed Judaism or Jewish history. Between 1974 and 1979, seminars of refusenik scientists operated in Kishinev and Leningrad.

Home seminars were conducted on legal topics as well. In Leningrad one took place in the apartment of the Taratuta family and another was held in Moscow in the apartment of Dmitry and Bella Ram. The former was directed by Valery Segal and the latter by Mark Berenfeld. The topics discussed were legal questions related to efforts to emigrate and to steps taken by the authorities to repress Jewish activity.

The emigration of many Zionist activists, combined with increased emigration of non-activists, led to a decline in Zionist orientation. More emigrants began to choose the United States and other Western countries over Israel as their destination. This phenomenon became known as “neshira” (Hebrew for "dropping out"). In 1976, the number of dropouts almost equaled the number of those who made aliya and, subsequently, the former predominated. One factor in the rise of the dropout phenomenon was fears about life in Israel in the wake of the Yom Kippur War (1973). Immigration to the West was spurred also by the agreement of some Western countries, e.g., the USA, to grant ex-Soviet Jews refugee status, which entailed special rights. The unleashing of an anti-Israel campaign in the Soviet mass media also made Israel appear less attractive to Soviet Jews.

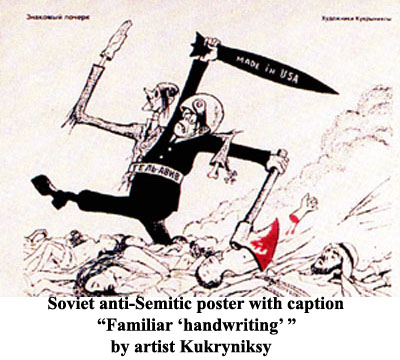

All references to positive roles played by Jews in history or to their persecution were eliminated from Soviet publications intended for a large readership, leaving only the image of the Jew as "the Zionist enemy." Anti-Zionist (i.e., anti-Semitic) literature was published extensively. From 1967 to 1985, 340 such books appeared. Authors began frequently to cite anti-Jewish statements by Karl Marx and to accuse Zionists of having collaborating with the Nazis. Zionism was presented as the incarnation of universal evil, a force that controlled Western economics and policies. Furthermore, Soviet publications repeated the myth of an international Jewish conspiracy and even mentioned the ritual murder accusation against the Jews.

Soviet anti-Zionist works were translated into many languages so they could be distributed both among foreign tourists in the Soviet Union and abroad, including in Arab countries. To a great extent this campaign has been a major factor in spreading anti-Semitism in the contemporary world.

The Jewish movement evolved within the context of growing opposition to the Communist regime, as exemplified by the rise of the dissident movement. The latter's influence on the Zionists was particularly strong in Moscow, where many Jewish activists, who had themselves been dissidents, retained ties with non-Jewish dissidents and learned from them ways to struggle against the regime. For example, the Jewish activists shared with each other two guidebooks by the dissident Vladimir Albrecht: “How to act during a search” and “How to act when being interrogated.” The advice contained there came in handy for many of them since the state security organs employed the same methods against the Jewish activists that they used against other dissidents. These included: surveillance, wiretapping telephone conversations or simply cutting off suspects' telephones, warnings by the KGB, beatings, searches, short-term arrests and, finally, longer imprisonments or sentences of internal exile.

Leading Jewish activists like Vladimir Slepak, Vitaly Rubin, Anatoly Sharansky and Naum Neiman believed that a common struggle against the regime of all opposition forces would be most effective. Others, who disagreed, in principle still sympathized with the dissidents but believed that cooperation with them would lead to increased repression against the Jewish movement. This, in fact, is what happened in the case of Anatoly Sharansky.

In the mid-1970s, Anatoly (Natan) Sharansky, a graduate of the prestigious Moscow Physics and Technology Institute, was one of the most visible activists of the Jewish national movement. He participated in seminars of refusenik scientists, signed and, even, composed protest letters to Soviet authorities and appeals to Western public opinion, and took part in demonstrations. From May 1976 he was a member of the Helsinki Human Rights Monitoring Group in Moscow. Sharansky was a spokesman to the foreign press, diplomats and political figures for both the refuseniks and the dissidents. It was through him that information about repressions of the Jewish activists made its way to the West.

On January 22, 1977, the film “Buyers of Souls,” which depicted Jewish activists, including Sharansky, as “paid agents of international Zionism,” was broadcast on national television. A month later, Izvestyia accused Sharansky and other activists of spying for the CIA. Then Sharansky was arrested. After an investigation lasting several months, Sharansky's trial resulted in a predetermined outcome: he was sentenced to 13 years imprisonment on the charge of espionage. During his incarceration, on several occasions he staged a hunger strike, one of which lasted 110 days. The campaign to release Sharansky, led by his wife Avital, made his name a household word. Heads of state raised the issue of his release at meetings with Soviet leaders. Finally, on February 11, 1986, Sharansky was freed in exchange for a Soviet spy who had been arrested by the Americans.

By the mid-1970s, fewer Jews sought permission to emigrate. The more nationally conscious Jews from the western regions of the Soviet Union had, by and large, already emigrated, while the majority of the more sovietized Jews were not yet ready to take the same step. Movement activists asked what could be done to increase emigration and to lower the dropout rate. Vladimir Prestin, Venyamin Fain and Pavel Abramovich believed that it was necessary to increase the national consciousness of broad segments of the assimilated intelligentsia by intensifying activities related to Jewish culture. Such activity was also favored by people, like Mikhail Chlenov, whose goal was the legalization of Jewish culture in the USSR since, in their view, aliya would not solve the problems of all Soviet Jews.

In contrast to the latter group, a small but influential group of "politicals" – Vladimir Slepak, Alexander Lerner, Anatoly Sharansky, Alexander Lunts, Dina Beilin and Ida Nudel – called for the Jewish struggle to be limited to the struggle for emigration. They advocated concentrating on the teaching of Hebrew. Otherwise, if the government permitted some aspects of Jewish culture that would create the illusion that the Jewish problem was solved and, hence, distract Jews from the idea of aliya. However, despite this concern, subsequent developments indicated that cultural activity attracted to the Jewish national movement thousands of Jews who initially were not interested in aliya but eventually did move to Israel.

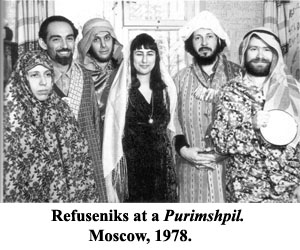

In addition to the teaching of Hebrew, cultural activities included the staging of amateur plays and purimshpils, the organization of festivals of Jewish songs, maintaining underground Jewish libraries, publishing samizdat journals of history and culture, the sponsoring of exhibitions of works by Jewish artists, and the holding of seminars on Jewish culture and, even, of scientific symposiums.

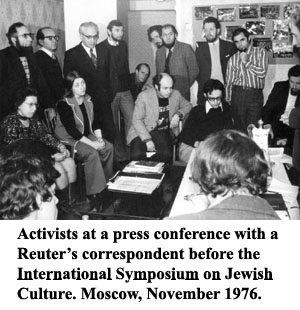

An international symposium, titled “Jewish Culture in the USSR: Its Present State and Prospects,” was planned to be held in Moscow on December 21-23, 1976. The organizing committee was headed by Professor Venyamin Fain and included Vladimir Prestin and Mikhail Chlenov, among a total of 13 activists from 10 cities. Invitations were sent to relevant official Soviet organizations, as well as to scholars and important cultural figures from Israel, England, Sweden and the United States.

The Soviet authorities declared the symposium “a Zionist provocation” and did everything possible to prevent it from taking place. The KGB searched the apartments of the organizers and confiscated everything that had any connection to Jewish culture. A wave of searches and interrogations in Moscow, Leningrad, Kiev, Minsk, Kishinev, Vilnius and Gorky followed. Measures were taken to block the arrival in the capital of Soviet citizens from other cities and foreign guests were denied entrance visas to the country. On the morning of December 21, all the members of the organizing committee and others who were suspected of wanting to attend the symposium were detained by the police and placed under house arrest. However, despite these round-ups, approximately 50 people, including Andrei Sakharov and his wife, met at a private apartment. They listened to some of the lectures prepared for the symposium and, then, proceeded to discuss them.

In Leningrad, 12 Jewish artists, including Yevgeny Abezhauz Alexander Okun and Tatyana Kornfeld, established a group called "Aleph." The group held two exhibitions, both in private apartments, one in Leningrad and in Moscow. One work, by Abezhaus, “Our Aliya,” pictured a flock of ravens flying over a twisted Star of David.

In the mid-1970s, Jewish samizdat began to appear in the form of periodicals rather than as isolated items. Moscow was its main center, with the samizdat journals, Tarbut (Culture, 1975-1979), Evrei v sovremennom mire (Jews in the Contemporary World, 1978-1981), Nash ivrit (Our Hebrew, 1978-1980), Vyezd v Israel: Pravo i praktika (Emigration to Israel: Right [theory] and Practice, 1970-1980), and others. The intellectual journal, Evrei v SSSR (Jews in the USSR, 1972-1979), published philosophical and historical essays, prose and poetry, and demographic and political studies. Following the dissident tradition, the cover of the journal indicated editors' names, addresses and telephone numbers. The first editors were Alexander Voronel and Viktor Yakhot, the last was Victor Brailovsky. As the most serious uncensored periodical of its kind, the journal made a historical contribution to the development of Jewish culture in the Russian language and, thereby, helped raise Jewish national consciousness. Twenty issues of the journal appeared.

Riga was another center of samizdat Jewish periodicals. Among them were the literary and journalistic magazines, Hayim (Life, 1979-1986) and Din u’metziut (Law and Reality), whose issues contained information about legal questions relating to emigration.

In the 1980s, after Moscow's role declined, Leningrad became the center of Jewish samizdat periodicals largely due to the appearance of Leningradsky Evreisky Almanakh (The Leningrad Jewish Almanac, often referred to by its initials LEA). Over the course of its 19 issues, between 1982 and 1989, the following people were editors of LEA: Yury Kolker, Semyon Frumkin, Mikhail Beizer, Victor Birkan and David Yoffe. In the face of increasing repression, the editors ceased identifying themselves and, also, avoided publishing overtly anti-Soviet materials, focusing instead on cultural matters. For a samizdat publication LEA's print run was large – 70 copies.

Perhaps the most widespread form of Jewish cultural activity was the teaching of Hebrew. In the early 1980s, in Moscow alone there were 100 Hebrew teachers, with more than 1,000 students. A "Hebrew week," in which perhaps a thousand people took part, was organized in Moscow, in March 1979, by Pavel Abramovich. Yuly Kosharovsky, who had moved from Sverdlovsk to Moscow, organized summer seminar-camps in Odessa, the Crimea and the Baltic states for teachers of Hebrew, while Alexander Kholmyansky and Yuly Edelstein coordinated ulpanim throughout the country. Among the Hebrew teachers in Leningrad were Valery Ladyzhensky, Yosif Radomysl'sky, Leonid Zeiliger, Roald Zelichenok and Semyon Yakerson.

The movement for emigration entailed serious expenses. Support was needed not only for Prisoners of Zion and their families but also for others. Money was needed for people who were fired from their jobs after requesting exit visas, for reproducing samizdat, for the celebration of Jewish holidays, for providing kosher meat and religious objects for those Jews who wanted them, and for covering some of the serious expenses connected with emigration.

In order to meet these needs, foreign aid was provided, in the form of packages, as well as money. Some tourists brought with them items that Soviet Jews could sell. A central role in this activity was played by the Israeli organization Nativ, which distributed financial aid that originated with the American Joint Distribution Committee. Also involved in providing aid from abroad were other foreign Jewish and non-Jewish organizations that fought for the rights of Soviet Jews. Significant among Jewish contributors from abroad was the Lubavich (Chabad) Hassidic movement. Aid intended for families of Prisoners of Zion was distributed first by Ida Nudel and, then, by Natalia Khasin. Aid for social needs was also distributed by Prestin, Kosharovsky, Aba Taratuta and a number of other leaders of the movement. Medicines from abroad were distributed by Lev Goldfarb and Inna and Igor Uspensky in Moscow, and Alla and Boris Kelman in Leningrad.

The moral significance of this help was great: it signified that the fate of Soviet Jews mattered to people abroad and gave strength to Jewish activists in their struggle with the Soviet regime.

The Soviet government used all means possible to halt aid from abroad, including the arrest of tourists and the confiscation of items they were bringing to Soviet Jews. In the second half of the 1970s receipt of money from abroad was halted and customs duties were raised significantly on the packages. Some Zionist activists were included in a black list that prevented them from receiving packages in any case.

On the eve of 1980 the Soviet army invaded Afghanistan. Détente between the East and the West ended. For Soviet Jews this meant the curtailment of emigration, which was marked by a long period of mass refusal.

One of the grounds cited for refusal was an “expert opinion” from a person's workplace, stating that the potential emigrant had had access to military or state secrets. Sometimes this was the truth but often it was a total fabrication. Sometimes OVIR, the body in charge of granting exit permits, attributed denial of permission to emigrate to the insufficiently close relationship of the applicant to the relatives in Israel. People were also refused when close Soviet relatives, like parents or former spouses, objected to their leaving. One vague explanation for denial of emigration was the claim that letting someone go did not “correspond to the interests of the state.” At other times, refusals were given without any explanation at all, and there were even “permanent refusals,” when an applicant was told “You will never leave.”

Refusals were always given orally. A document was never provided stating the date of refusal or the length of time it was supposed to be in effect. Attempts to appeal would lead the refusenik into the exhausting Kafkaesque labyrinth of Soviet bureaucracy. Often OVIR created pretexts to avoid accepting emigration requests. One trick involved the post office's failure to deliver invitations from Israel to potential emigrants. Since they well understood which way the wind was blowing, many Jews decided to wait for better times before seeking to leave.

Once an applicant was refused, it was impossible to return to a normal Soviet life. As a result of seeking to emigrate, many people lost their positions as highly educated and qualified personnel. Whole families were frequently deprived of their means of survival. Young Jewish male refuseniks faced the prospect of being conscripted after losing their student exemptions when they were expelled from university. When they completed their army service, they were sometimes refused emigration permission again, this time allegedly for having had access to military secrets.

The majority of refuseniks waited seven to nine years to emigrate, while others were in refusal from 15 to 18 years. The most long-suffering family was that of the Bessarabian Jew, Faivel Gorodetsky, who first applied for emigration to Israel in 1964. The family was finally given permission to leave a quarter of a century later.

When only some members of a family were allowed to emigrate, both the refuseniks and the fortunate emigrants had to endure long periods of separation. Very ill refuseniks lost hope for medical treatment in Israel. For example, the Leningrader Yury Shpeizman, who suffered from lymphomic cancer, received permission to emigrate only after a struggle of many years. He died in Vienna on the way to Israel. Inna Flyorov of Moscow was not permitted to go to Israel to contribute bone marrow to her brother who was ill with leukemia. For middle-aged refuseniks the most productive years of their lives that could have helped them adapt to a new country were lost and the professional qualifications they had obtained through years of study and productive work were wasted.

Often refuseniks found themselves isolated socially. Loyal Soviet citizens who had been friends or colleagues excluded refuseniks from their social circle. Even close relatives sometimes avoided them, fearing harm to their own careers and worrying about protecting their children from "bad influences." In the difficult situation of refusal, families sometimes fell apart, for example, when one of the spouses blamed the other for starting their ill-fated emigration effort. Some people were even co-opted by the state security organs in return for a promise of an exit visa. Others tried the risky tactic of bribing OVIR officials to expedite their emigration request.

At this time, when the refuseniks numbered in the tens of thousands, the importance of cultural activity increased. An especially popular home seminar in Leningrad on Jewish history and tradition was headed by Grigory Kanovich, Lev Utevsky and Grigory Vasserman. The KGB persecuted those attending the seminar: at one lecture devoted to Israel’s Independence Day the mathematician Yevgeny Lein was arrested and charged with attacking a policeman.

In 1982, Mikhail Beizer organized an ongoing scholarly historical and cultural seminar. The lectures were subsequently reworked into articles and regularly published in the LEA. In addition to the refuseniks, one participant in the seminar was the prominent ethnic Russian historian and ethnographer, Natalia Yukhneva. Seminars on Jewish culture took place also in Moscow, Kharkov, Kishinev and Riga.

During this period of mass refusal, Jewish consciousness was also fostered by the sessions of Moscow’s Jewish Historical and Ethnographic Commission, which was associated with the Yiddish journal Sovetish heymland (Soviet Motherland), and headed by the ethnographers, Mikhail Chlenov and Igor Krupnik.

Another useful form of cultural activity was the organization of secret Jewish libraries for the general Jewish public. One of the first was established in Leningrad, when Aba Taratuta succeeded in obtaining a private collection of old Jewish books and journals.

Considerable popularity was enjoyed by amateur purimshpils, where the biblical history of Mordechai and Esther was updated. The plays not only presented a humorous treatment of the daily lives of the refuseniks, they also made fun of the Soviet regime and its persecution of Jews. The audiences were encouraged to hope that the Soviet "Hamans" would receive the punishment that they deserved. Authors of the first refusenik purimshpils were M. Nudler in Moscow and Boris Lokshin and Valentin Feinberg in Leningrad. Producers included the Leningraders Mikhail Makushkin, Elena Romanovsky and Semyon Frumkin, the Muscovites Lev Kanevsky, Igor Gurevich, Alexander Ostrovsky and many others. Leonid Kelbert created an amateur home theater in Leningrad that staged the play “Masada” by V. Feinberg.

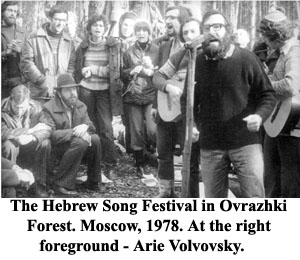

A forest clearing three kilometers from the suburban Moscow railway station of Ovrazhki was chosen by Anatoly and Yevgeniya Shwartsman for shared Sunday recreation and Jewish activities in early 1976. Ovrazhki became a site for mass gatherings of refuseniks. Classes on Judaism and on Jewish history were held. There were Jewish song competitions, and celebration of Jewish holidays, as well as sporting events and picnics. After more than a thousand people gathered at Ovrazhki in May 1980, however, the KGB took steps to prevent further mass Jewish activity there.

A Zionist-oriented group called Jewish Women against Refusal was established in Moscow in 1986. Its 13 members included Inna Uspensky, Mara Abramovich and Yelena Dubyansky. A non-Zionist group called Jewish Women for Emigration and Survival in Refusal, whose members included Judith Ratner, Nelly Mai and Bella Gulko, was also founded. The women focused on family problems caused by refusal and attracting the support of international women’s organizations for the struggle of Soviet Jews for emigration. Despite their differences, the two groups participated jointly in demonstrations, press conferences, and meetings with public and political leaders from the West. In addition, they held a hunger strike in conjunction with International Women’s Day.

Some refuseniks turned to religion. It was difficult for religious Jews to function in the USSR, which did not allow the Jewish Sabbath to be a day of rest, where it was often impossible – due to the distance – to walk to the synagogue on the Sabbath or holidays, and where kosher food was hardly available.

Among the first hozrim b'teshuva, or newly-religious Jews, in Moscow were Karl Malkin, Pavel Goldstein, Nathan Feingold and Eliyahu Essas, who established a Torah-study group in 1977. Subsequently, another group to study Torah was set up in Moscow under the leadership of Vladimir (Zeev) Shakhnovsky. In Riga, in the late 1970s, Mendel Gordin and Yosif Mendelevich became religious.

A majority of the newly-religious Jews were affiliated with the Chabad hassidim, while others identified with the Lithuanian misnagid tradition. Leaders of the Chabad group were Grigory Rosenstein and Zeev Wagner in Moscow and Yitzhak Kogan in Leningrad, and leaders of the "Lithuanians" were Essas and Shakhnovsky in Moscow and Grigory (Zvi) Vasserman in Leningrad. In 1982, a book by Grigory Rosenstein and Mikhail Shneider, Ya veryu (I Believe), which presented the basic ideas of Judaism in accessible form, appeared in samizdat.

In the late 1970s, the astrophysicist, Vladislav (Zeev) Dashevsky, gathered around him a group of Moscow high school students. He taught them Torah, Jewish philosophy and Jewish history. In addition to Dashevsky there were other teachers, including the more advanced students, like Pinkhas Polonsky and, sometimes, guests from abroad. In time, the group became a movement known as "Mahanayim," a Hebrew word meaning “two camps,” in reference to Moscow and Jerusalem. A majority of the teachers of Mahanayim are now in Israel, where they are continuing their educational activity.

In conclusion, by the mid-1980s that inaugurated the final years of the Soviet Union, the refuseniks had established a basis for an independent Jewish public, religious and cultural life, which flourished during the years of perestroika. Although Mikhail Gorbachev proclaimed a new political course in the spring of 1985, arrests of Jewish activists continued. Reform in the Soviet Union began to have an effect on the Jewish street only a couple of years later. This could be seen in the demonstration of seven Leningrad refuseniks that was held in March 1987. Not only was the protest not broken up, but it concluded with the demonstrators being invited to discuss their problem with the obkom (provincial committee) of the Communist Party. Another unprecedented aspect was the fact that a photograph of the demonstration appeared in the city newspaper, Vecherny Leningrad.

Soon after aliya was renewed the Prisoners of Zion were freed from jail. By late 1989, almost all the long-term refuseniks had been allowed to emigrate. The authorities ceased harassing ulpanim for teaching Hebrew and samizdat publications. First in Tallinn (with Shakhar [Dawn]) and then in other cities, independent Jewish periodicals began to appear openly. The government also legalized Jewish cultural, educational and public organizations. In December 1989, the founding meeting of Va’ad, the Federation of Jewish Organizations and Communities of the Soviet Union, took place in Moscow.

During the 1990s, the majority of the Soviet Jews emigrated to Israel.

Translated from Russian by Yisrael Elliot Cohen.

Site editors’ note: This material is a version of the Michael Beizer’s article included into the Exhibition Catalogue, edited by Rachel Shnold and published by the Beit Hatefutzot (Diaspora Museum), Tel-Aviv, 2007. The illustrations are from the Remember and Save Association’s archive and from the Catalogue.