Excerpts from the book

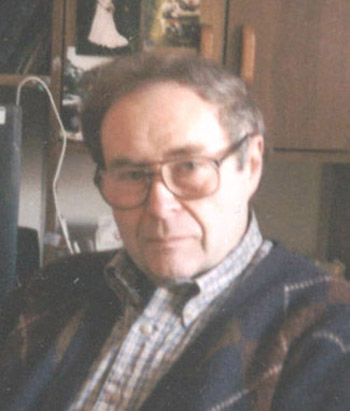

Born in 1936, in Kharkov, Yuri graduated from Kharkov Politechnical Institute, moved to Krasnoyarsk,

completed his Ph.D. thesis at Moscow Mendeleev Institute in 1963, and defended it at the Academy of Sciences, Institute of Organic

Chemistry, Novosibirsk. He was a professor of organic chemistry at the Siberian Institute of Technology, Krasnoyarsk until 1977,

when he learned that the KGB was closely watching him. At this point he decided to emigrate, spent two more years in Kharkov and

applied for exit visas for himself and his family in 1979. He was also one of the organizers of cultural and scientific seminars

of refuseniks in Kharkov, a Jewish mini-university for their children, wrote letters of protest, made contacts with Western

journalists, and held a group hunger strike in his apartment. The leaders of the group included Alexander Paritzky, Eugene

Chudnovsky, Isaak Moshkovich, and David Soloveychik. Yuri held a 40 day long personal hunger strike in 1982 and was arrested in

March, 1983. He completely ignored the investigation and trial, except for the last word, and was sentenced to 3 years in a

labor camp for slandering the Soviet system. After being released in March, 1986, from Chita (Siberia) labor camp, he left the

country in February, 1987 and went to Chicago. After a year he moved to Rhode Island, where he now lives with his wife, Olga.

In the USA he worked for chemical companies as a research scientist before retiring in 2001. Current occupations: writing essays

and poetry in English and working on a new direction in artificial intelligence with a local university.

Personal web site: http://users.ids.net/~yuri/POETRY.html

When I was lying on the rocky concrete of the devils' cell, I was given the fascinating gift of flying. Writing this book, I am captivated by another curious phenomenon. All the people I met in Russia — friends, enemies, dybbuks, and even the ignorant zeks — all of them speak English. I see their faces, hear the unique modulation of their voices, but they talk to me in English. I speak English to them, too.

I can retrieve the smells and colors of the camp, my visions are vivid, and I even feel that the memories of the past crinkle up my face into a scornful and callous mask.

The language in my ears, however, is evidence that I have been undergoing a cataclysmic transformation. I am probably still in the process of it. I observe in myself the battle of the two greatest elements of life — past and future. They clash like hot lava and sea water. The past cools down, forever solid. The future recedes a little, forever fluid.

The voices and visions are just daydreaming.I am typing these lines on my computer. I see the Latin characters on the screen. I am free. I am in America.

What can be greater than the transition I am in — from slavery to freedom? I was wading chin deep in water in my nightmares. Here, I walk chin deep in freedom. No one around me can feel the freedom as I do. It is as material and tangible as the rain. It is antipressure, antimatter, antiresistance, antisuffering. Oh, Lord! I am still too Russian. A negative form always comes to mind first. Slavery is still primary for me. Probably, it must be so.

I am happy I was a slave. Thank God I was a slave! There is no light without darkness, no heat without cold, no satiation without hunger, no health without illness, no freedom without slavery.

I knew happy times in slavery, I know sad times in freedom. As Plato said, we cannot say that somebody is happy until he dies. Whatever else is going to happen to me, I am happier than those born in freedom because I was privileged to experience the painfully sharp delight, the mellow penetration, the sweet shock of transition from slavery to freedom. My feeling of freedom is ever acute and piercing. My love of freedom is not platonic anymore.

I firmly expected to encounter anti-Semitism in the labor camp for which I was heading. Serge, my wonderful thief-professor in the Kharkov prison, had told me in the very beginning that there was no anti-Semitism in Soviet prisons and camps. "All nations are equal behind bars," he used to say. But there in the Ukraine, where anti-Semitism was as organic to the mentality as borscht was to the national diet, I could not believe it.

If the truth be told, I never witnessed or was subjected to any ethnic hostility in the Ukrainian prison. Neither did I feel myself a Jew in three transit prisons and later in the labor camp. After four years of stewing in the cauldron of Jewish refuseniks, however, I found that inevitably Jewish problems would often come to mind.

As I have said, being Jewish was considered a nationality, not a religion, in Russia. I was listed as a Jew on all forms and documents, and even if I wanted to — which I never did — I could not change that. Had I become a faithful Christian or Muslim, my papers and my status would not have changed a bit. No one ever asked what religion an individual actually practiced when personal papers were being filled out. The state pretended it did not matter.

I had entered the refusal without any particular interest in Jewish problems. I wanted to go to America to be free, not to be a Jew. But then our seminars in Jewish culture revived my interest and involvement. It was in the refusal that we held our first Passover Seder and celebrated other festivals. I had access to the literature that I would otherwise never have found and I quickly became absorbed. It turned out that for me being free included being a Jew.

Judaism seemed more rational than any other religion known to me, with a beauty similar to mathematics. It started with a system of axioms presented in the Torah — the first five books of the Bible — and the rest was just logically derived from the axioms. Even the Hebrew language seemed an evidence of creation, not evolution, because it was based on a three-letter root code, like the genetic code in biology. It could not be an accident, I thought.

At that time I made one of the biggest personal discoveries of my entire life. The Jews had invented the love of one's neighbor and humanism in general. Before I had always thought it were the Christians. I discovered that my own moral values, which I had not always followed but always cherished, were of Jewish origin. I admired the non-intrusive negative formula of Judaism: "Do not do to your neighbor what you do not want to be done to you." I did not want my neighbor to do to me what he considered right for himself. It seemed to me that the cult of human thought itself had been developed by the Jews. I kept thinking about all I had learned.

When, after some study of the language, I started reading the Torah in Hebrew, I was thrilled by another discovery. I had thought that the power of the most ancient modern book was a trick of translation, that the original had to be dark and primitive. But my own translation was unambiguous: "First, God made the skies and the land."

Although I gradually lost some of my sensitivity to it, the memory of the Holocaust, even if more destructive than constructive, shaped my generation of Jews. What I learned had nothing to do with the Holocaust, which had dominated my awareness of myself as a Jew before.

What I discovered in my forties was not a new mix of delight, captivation, pride, or any other familiar components. It was a completely new constituent. The Judaism I proudly discovered was my first positive Jewish self-image, more positive than my Russian idea of freedom. It was a feeling of belonging to a chain of generations, a feeling as elemental as the feeling of having a brain or of being alive.

In Rome, on my way to America, I met a woman from Israel who was the sister of a famous refusenik, at that time still held captive in Russia. I was overwhelmed by her anger against all Jews who did not live in Israel.

"Those who stay in America are not real Jews. Only we Israelis are real Jews. The American Jews think we should be grateful to them for their help. We can do without them. We don't need their help. They should be grateful to us because we fight for them. They must go to Israel if they consider themselves Jews. You too must go to Israel. Only traitors go to America."

Her words smacked of typical Soviet mentality. "There is only one truth, and only we know it, and if you are not with us, you are our enemy." That was the very essence of every totalitarian and despotic ideology.

She was the second Jewish chauvinist I had met, after Machine Gun Jacob.

"On the one hand, yes, we are all Jews; therefore you should help us. On the other hand, no, you are not really Jews; therefore, don't poke your nose into our politics."

I can vividly imagine a Jewish commissar in a black leather jacket with a Mauser speaking Russian with a Yiddish accent, knowing very well that he who is not with us is against us, inebriated by power after the subjugation of the shtetl, holding the great revolution, and shooting the enemies of the people.

Gary's uncle was a famous red commissar, and his name was mentioned in textbooks of Soviet history. So was my aunt Sara. The colors of the young people from Irgun were different — white and blue. Bright and courageous, they could sacrifice their lives, but with the same nonchalance they could splash the red on the white and blue and sacrifice the lives of others without asking for consent.

In Kharkov, when our first puppy died of distemper, I was very upset. I told my friend Leo, who was later sentenced for refusing to testify at my trial and who also happened to love dogs, "She did not even know what summer looks like."

"Take it easy; it is just a dog," he said.

The same year, I discussed Israeli's invasion of Lebanon with Leo. I was worried that the invasion would cast a shadow over the image of Israel. "Take it easy," Leo said. "They are just Arabs."

The Gulf War, although Israel did not take part in it, had a much stronger impact on me than the war of 1967. For the first time I realized what kind of neighbors Israel had to deal with.

I saw very clearly that Israel had no other choice but to be strong and to defend herself. Israel and her neighbors were as incompatible as Americans and Soviets.

Like an individual, the country that has no choice is not free. The choice between life and death, however, is beyond freedom and beyond any philosophy. It is just physiology.

All my life experience has taught me that we have to take a stand. I cannot accept the Russian "on the one hand, yes; on the other hand, no." I would not hesitate to take sides. Still, the conflict between physiology and philosophy has always been a sad issue for me.

During my last year in the camp I had an opportunity to better understand what kind of physiological choice a besieged nation can have. I felt it on my own skin, and it was another illustration of my fixation on the similarity between a person and a country.

Excerpts from the book: Yuri Tarnopolsky, Memoirs of 1984, Lanham, MD: University Press of America, 1993

© Yuri Tarnopolsky, 1993