Four years ago, sitting in an apartment in Moscow, remember vividly the unpleasant impression, amounting to fear, which came over the two refuseniks in the room with me (both of whose husbands were then prisoners) when a friend telephoned them to say that the Moscow newspaper Vechernaya Moskva had just published an article denouncing those Jews who received visitors from the West.

According to the article, these "so-called tourists" had in fact been sent to the Soviet Union by "foreign Intelligence." Behind them, so it was alleged, stood first and foremost the Central Intelligence Agency in Washington, misusing the Helsinki Agreement by infiltrating these tourists in order to recruit agents "among renegades and corrupt individuals who are outcasts from Soviet society - who have not found a place in our Soviet family."

The article went on to give several examples of these outcasts. Most of them were dissidents or war-time collaborators with the Nazis. Two, however, were refuseniks, Anatoly Sharansky - then less than halfway through his 13-year sentence - and his friend Vladimir S1epak, at that time only recently released after five years of Siberian exile. According to the article, Slepak, although then in Moscow, was still a "Zionist agent" working on behalf of the Israeli secret service.

This article in Vechernaya Moskva represented not the mere private opinion of the writer, but official policy. Just over a month ago. this same newspaper struck a blow at refusenik hopes when, on February 12, it published a special boxed article giving the names of eight Jews who, it said, "as bearers of State and military secrets," would never leave the Soviet Union.

One of those named in the list, Natasha Khassina, had complemented Ida Nudel's role as a lifeline of moral support for the prisoners and their families. Another of the eight, Lev Sud, whom I met in Leningrad in August 1985, is a religious Jew, whose brother-in-law lives in Jerusalem. A third of the eight, Vladimir Slepak, the same Slepak described as a traitor four years before, has now been refused his exit visa for 17 years. From Friday, March 27, Slepak's son Alexander will begin a 17-day hunger-strike in Washington in protest against his father's 17 years in refusal.

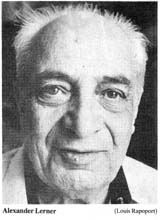

Year after year, Slepak has watched as one by one his friends have been allowed to leave the Soviet Union. But not all his friends: another of those singled out by Vechernaya Moskva was Professor Alexander Lerner, who first applied to live in Israel within a year of Slepak's application. I feel a strong personal link with Professor Lerner, whom I also met in Moscow in August 1985, and to whom I dedicated my recent book The Holocaust, the Jewish Tragedy.

Professor Lerner's two daughters were murdered by the Nazis on Soviet soil in 1941. Now, at the age of 73, he is a widower, whose only surviving daughter lives in Israel. Commenting on the article of February 12, Professor Lerner said: "I have rarely been quite so angry as when I saw the boxed announcement in the paper. While, for some of us it was the first written reason for our refusal, and to that extent welcome, it was nevertheless a gross distortion of reality." Lerner added, of the so-called secrecy classification: "It is clear that for all of us such categorization is bureaucratic lunacy, or plain vindictiveness. To publish things like that caused all of us deep distress. It is humiliating mental cruelty."

Another of those named in the Moscow newspaper is Yuli Kosharovsky, a Hebrew teacher of distinction and a man of great charm and courage. Like Professor Lerner, he first applied to leave the Soviet Union in 1971. His three children have spent all their life as refuseniks. His wife Inna has dreamed of bringing them up in Israel.

Soon it will be Passover. Last Passover, Kosharovsky wrote to me: "Year after year the desert dispersed us all over the world. And some go through the real devil. And still, our hearts beat as one, when we think and re-enact the Exodus.” As for the Jews of Russia, he added, “Sometimes I have a feeling that we are just crossing the Red Sea now. Quite dangerous. But when we see our friends on the other side, giving us your hands, we understand that we will pass over."

Kosharovsky was 29 years old when, on 10 March 1971, he first applied for his exit visa. Like Lerner and Slepak, he was refused on secrecy grounds, even though, as long ago as 1974, he was told that the secrecy restriction no longer applied in his case. When he received his second refusal, now 13 years ago, he was told that it was a "punishment" because he had become an activist.

Yuli Kosharovsky is now 45. His many friends in Israel and the West can only ask, in the name of whatever new winds are blowing in the Soviet Union, that his family, together with seven other families named in the demoralizing article of February 12 can be allowed to leave as soon as possible. If they have to remain refuseniks, what meaning can there be in all the talk of a new exodus?

Published in “The Jerusalem Post” of March 24, 1987.