A hero for our seder

MICHAEL SHERBOURNE

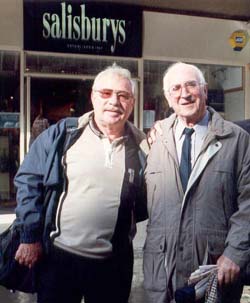

Michael Sherbourne (right) and Si Frumkin

|

By Si Frumkin

Si Frumkin was born in Kaunus, Lithuania, and spent his childhood there - because of that he has a perfect command of Russian.

When the German army invaded Lithuania, Si and his family were deported to a concentration camp. He alone from his family survived,

was liberated from the camp and came to USA. He lives now in Los Angeles. From the beginning of 70-s he serves as a Head of the

local Committee for the free emigration of the Soviet Jews.

|

|

I don’t remember how long ago it was that Michael visited Los Angeles. 15 years? 20? I do remember that I was driving him around the city when he said, “Could you stop the car for a moment? I would like to photograph this.”

I was puzzled. “Photograph what?” I said. There was nothing remarkable that I could see. Michael laughed. “The street sign, of course. They named a street after me.”

Sure enough. There it was. Sherbourne Drive. I am certain that whoever named it had never heard of Michael Sherbourne. A pity. He deserves having a street named after him.

Later that day told me of another honor. “I am probably the only Jew who was promoted to a member of the British nobility by a communist newspaper,” he said. In the 1970s, “Pravda”, the major Soviet newspaper, ran a lengthy editorial about that “Zionist provocateur and a typical representative of the rotten British ruling class, Lord Sherbourne.” Michael never asked “Pravda” for a correction. The truth is that Michael’s father who escaped from Czarist Russia to England was a sailor on a British merchant vessel in 1914 when England went to war with Germany. The other sailors gave him a hard time because they though he was German - his name was something like Ginsburg or Friedman. When the ship returned, Michael’s father got a copy of Burke’s Peerage, a listing of all the titled names, found a name he liked and had his name changed to the, oh-so-very British Sherbourne.

Michael and his wife went to a kibbutz in British-ruled Palestine in the 1930s. He joined the Navy when war broke out and later ended up teaching French and metal shop at a London high school. It was there that he accepted a challenge that changed his life. A colleague sneered at French as a language. It was too easy, he said. “Now, Russian is a tough language. I bet you couldn’t learn Russian,” he taunted.

Michael smiles when he tells the story. “It was tougher than I thought,” he says. “I was in my 40s by then and I almost gave up a few times. But I did it eventually.”

He did indeed. Last time I saw him was in London in 1999. My formerly Muscovite wife Ella, Michael and I were having a sandwich in a London deli, with Michael chatting away in pure and fluent Russian with Ella. She asked him if he liked Russian literature and what he thought about the great Russian poet Pushkin. “Pushkin?” Michael said. “I love Pushkin. His poetry is like music. Just listen…” And then he began reciting “Evgeny Onegin”, chapter after chapter, by heart, without a pause.

In the 1960s and 70s, when the Soviet Jewry movement in the West was born as a reaction to Soviet anti-Semitism, Michael Sherbourne became the voice of the Jews in the West to the refuseniks and activists in the USSR. He made hundreds, maybe thousands of phone calls in Russian to the Jews who didn’t know whether their voices were being heard in the West. Michael knew the phone numbers and names of all of them – all the activists who were harassed, arrested, tried and sentenced by the authorities who couldn’t understand what motivated the handful of Jews to fight the Soviet superpower. He was the indirect conduit and lifeline to thousands of others. The information he gathered helped us fight the Soviet Jewry battle in the West.

He used different names but the authorities knew who he was. An operator in Moscow told him so when he pretended to be a Russian engineer calling from Dniepropetrovsk. “We know who you are, Mr. Sherbourne,” she laughed.

Michael called me a few months ago to tell me that he was coming to spend the Passover with his granddaughter who lives in Washington, DC.

“Why don’t you come and join us for a Russian Seder in Los Angeles,” I asked. Michael was surprised. “A Russian Seder?” he asked.

I explained that Los Angeles has been celebrating Passover with a community Seder for the last 10 years. It started out as a joint project of the Bureau of Jewish Education, the Southern California Council for Soviet Jews and the Association of Soviet Jewish Émigrés. We produced a Russian-language Haggadah, invited Svetlana Portnyansky, a major international singing star to serve as our cantor, and I appointed myself to conduct the evening. The first year about 150 people showed up. They were senior citizens with vague childhood memories of Passover. As time went on attendance grew year after year and more younger people and children came. For the last three years we had to have it on both nights to accommodate the more than 600 we have room for. This year we had it at Temple Emanuel in Beverly Hills on April 16 and 17. Over 650 attended and about 35 more would have come if we had room for them.

There was a moment of silence on the line. “A Russian Seder? Really?” And then, “I would love to come.”

And so, on April 17, 86-year old Jewish hero, Michael Sherbourne, had a chance to take a look at what the challenge by a colleague 35 years ago had wrought.

I wish I could add “Michael” to the Sherbourne Drive street sign so that there really would be a street here named after him. He deserves it. And he doesn’t need to be a real Lord to be one of the noblest men I have ever known.

Los Angeles, 1993

Site editors note: In our archives we found a cutting from The Jerusalem Post of March 15, 1990. We decided to add it to this remarkable essay by Si Frumkin as it so accurately characterises his hero, Michael Sherbourne.

ETYMOLOGY OF REFUSENIK

To the Editor of The Jerusalem Post

Sir, - I was glad to see the recent letter on Howard M. Weisband of the Jewish Agency, correctly protesting about the issue by journalists of the word “refusenik”. I believe your readers may be interested to know a little more about the history and background of this neologism.

I am the person who coined this word and first used it in 1971. Late that year, during one of my many telephone conversations in Russian with Jews in the USSR who were denied permission to emigrate to Israel, the word “otkaznik” was used and as I said that I did not know this word, the speaker in Moscow, Gavriel Shapiro, translated it for me into Hebrew as “siruvnik”.

When I wrote up my report on this conversation, I had some difficulty putting this word into English, but after some thought I finally came up with “refusenik”, basing it on the use of foreign words to which the Russian suffix had been added, such as kibbutznik, moshavnik, mahalnik, mapainik, nudnik and so on.

The correct meaning is, of course, as Mr. Weisband justifiably points out, "A Jewish citizen of the USSR who has been refused permission by the Soviet authorities to leave the Soviet Union." To use the word in reference to a person who "is refusing to go somewhere, or to do something" is a gross misuse of the word, and is confusing the active with the passive.

I am glad to tell you that this word has now acquired international usage, and is employed in this spelling in French, Dutch, German and Italian, as well as occasional usage in Russian. Moreover it appears in a number of English dictionaries, notably Chambers Longmans and Collins. And after my writing to them, the publishers of Webster's (Collegiate and International), Random House, and the OED have all accepted my definition as above, have promised to correct it in the next edition, and also accept that the occasionally seen “refusnik” is not an alternative but a misspelling.

MICHAEL SHERBOURNE London.

Site editors note: The letters from Howard Weisband and Michael Sherbourne appeared in response to the misuse of the word "refusenik ("siruvnik" in Hebrew), by some Israeli journalists in reference to soldiers choosing to refuse to serve in army units deployed in the so called "territories".