The Jew in his Home

Part 4.

Vladimir Lifshits

Translated from Russian

by Ilana Romanovsky

Instead of an Introduction

Dear readers, this part of my memoir are devoted to our life in Israel. It was written during the Coronavirus lockdown, March-July 2020, when I, together with other Israelis, had to stay at home round the clock. A lifestyle like this encourages writing.

First Steps in Becoming Israelis

On our last day in the USSR, when all the household utensils had been already packed and sent to Israel, we decided to treat ourselves to our first family meal in a restaurant. Leningrad is a big city with lots of restaurants. We tried some of them, but everywhere we were told that this particular restaurant served only foreigners or simply that it was full. When we got hungry, we bought walnut buns in a shop near our house and ate them in the street, right under a huge poster telling everyone that the 70th anniversary of the Soviet Power was almost there. But a farewell meal in this style could not ruin our excellent mood.

On November 1, 1987, we left for Israel. Our family included Anya's mother (aged 74), Anya (42), Borya (aged 20 - in Israel he changed his name to Baruch), Masha (twelve) and I (aged 46). In the Leningrad airport we were subjected to a meticulous personal examination. It turned out that the pin that my mother had given to Masha was made of gold, and it was forbidden to take it out of the Soviet Union. We gave it to friends who came to see us off and were standing behind the screen. After that, they took me to a separate room for a personal search, where I had to get undressed and have my clothes thoroughly checked. It turned out that my trouser belt was part the Soviet army uniform and was not supposed to cross the border. Suddenly, the man who was sitting in silence in the corner of the room, said: "Give him his belt back, otherwise he will board the plane without trousers". They returned the belt to me, and I went to the plane with my trousers on.

At the airport of Vienna, with Sara Osatsky.

|

In Vienna we were met by Sara Osatsky from kibbutz Ramat Menashe and our Dutch lawyer, accompanied with two reporters. The reporters took hold of me and kept asking me questions up to the last minute before the take-off. Sara took Masha around the airport shops. Impressed by the abundance of the goods she had never before seen, Masha said: "In the USSR they told us that everything was for the people, but real life was poor".

In the Tel Aviv airport, we received a typical Israeli warm welcome, where solemn speeches were mixed with spontaneous joyful dancing. Right in the airport we received Israeli identity certificates, money allowances for the first month and a warrant for the absorption center that we had chosen, in a Jerusalem neighborhood called Gilo. The landscapes on the way there were beautiful - hills everywhere, and then, on top, the white-stone Jerusalem.

Hearty welcome at the airport in Israel.

|

In the absorption center they offered our family of five a three-room apartment on the top floor. I objected - Anya's mother would find it difficult to climb the stairs. They assured me that we would stay there only until the morning, and then everything would be settled. At that moment, some inner voice prompted me one of the basic Israeli principles: There is nothing as constant as temporal solutions, and I said that we could wait right in the office. For some reason the administrator did not like this idea and he promptly found two apartments on the first floor. In the morning, we found out that in our joy and confusion we had left behind one of the suitcases - and we could go to collect it only next week. On the very first day, people with whom we had exchanged letters from Leningrad came to see us. One of them was Lev Utevsky, who warned us that we had to behave ourselves, because G-d was very close.

The life in the absorption center left very good memories. Apartments were small but they were equipped with all the necessary amenities. They had balconies looking at Jerusalem's best sights. The absorption center held Hebrew classes for newcomers from different countries. The teachers were friendly and kindhearted. In addition to teaching us Hebrew, they aimed at giving us some understanding of our new country, which was especially important, since we found ourselves in a world that was totally new for us. In the beginning, it resembled the childhood, when everything surprised us: the sky that was always blue, the great variety of people's faces and clothes, the numerous shops with various goods and no lines for them.

The first months in the country were the time of a never-ending flow of celebrations, but also of serious problems and very intensive studies. Seeing people from Israel and other countries who had supported us during the years of struggling for the right to repatriate to Israel was a feast each time. Kibbutz Ramot Menashe sent a car for us and the day that we spent there was full of joy and special meaning for us. The kibbutz gave us six months' fare tickets for all the buses of Israel, and that was really helpful, because transportation was very expensive for us at that time. There were excursions for new repatriates, and we saw many beautiful places and learned a lot of new things. We liked the Hebrew classes, too. It turned out that even I, who had always found learning any foreign language a big problem, was able to enjoy learning Hebrew.

With Boris and Dina Ginkover (left to right: Dina, Boris, Vladimir, Anya).

|

This feeling of joy was mingled with a constant need of solving everyday problems. In a split second, we had to learn how to open a bank account and use a credit card, for when we were leaving the USSR, there was nothing like that there. The principles of medical service in Israel differed from those in the USSR. Even to find a certain office according to its address was sometimes a difficult task. In Jerusalem at the end of the 80-ies, many houses did not have numbers, crossroads did not have names of streets, and the streets themselves often changed their names after a couple of blocks. It took us several years to understand the Israeli bureaucracy. We had to deal with all these problems with very poor Hebrew. The new Aliya was only starting, that is why most people to whom we turned for guidance just did not understand our problems. Boris and Dina Ginkover made a helpful contrast. Boris was my age and we grew together in adjacent rooms in a communal apartment [an apartment where several families share kitchen and bathroom facilities - translator's note], and his wife Dina we met in Israel. They had come to Israel six years before us and seemed to us experienced Israelis. In many cases, they just took us to places we needed in their car and did all the talking for us.

Here is an episode that I remember from our first days in Israel. We stood at the cheese counter in a store in the center of Jerusalem and could not decide which cheese to buy, because we could not find the price list, and prices were the decisive factor for our choice. Quite unexpectedly, the shop assistant addressed us in Russian, which was a rare case in 1987. She explained that the prices could be found on the board hanging on the wall. Then she asked us when we had come and said, "Love this country. If you do not love it, the country will survive anyway, but you will find it difficult to live in it". We had luck - we learned to love Israel. From the first days, we felt that it was our home. We never saw Israel as an ideal country - we were aware of its faults and drawbacks, but this was our home. Sometimes we talked about Israel's drawbacks with our Hebrew teachers. They explained to us that every wave of newcomers made the country better while solving their own problems, and now it was our turn.

I remember a phrase that we heard in those days: "Israel is a free country, you can do whatever you wish here, but you have to pay for everything".

When we came to Israel, Masha was twelve. She has a talent for languages. She had started to learn Hebrew in the USSR, at first together with us, in Zelichonok's group, and then she taught herself from books and song records which we received from Israel. A couple of months in a Hebrew class for children was enough for her to be prepared to study in an Israeli school in Hebrew. Dina Ginkover taught in one of the best schools in Jerusalem, and she recommended Masha to try to get enrolled there. Masha passed the entrance exams well and was admitted to the school. In the first years, she was the only student at that school who was a newcomer from the USSR, and the good attitude of students and teachers to her helped her to feel at home there.

When Borya was not admitted to a Soviet school of higher learning, because we wanted to go to Israel, the Beer Sheva University asked for his school-leaving certificate and on the basis of it, enlisted him as a student even before our arrival in the country. The Boston University in the USA did the same. After our arrival in Israel, both universities confirmed their decisions. Borya declined the offer of the American university. He was enlisted in the Jerusalem University preparatory course, even though the enlistment had been completed long before that. After several months of learning at this course, Borya left for Beer Sheba.

In the beginning of 1988, the number of repatriates from the USSR started to grow gradually. It was necessary to convene a representative organ whose opinion could get attention of both Israeli authorities and numerous Jewish organizations abroad that wished to help our absorption. The Zionist Forum, which was organized in April 1988, became a body that met these criteria. The chairperson was Nathan Sharansky, and the presidium of the Forum comprised several prisoners of Zion, who had come to the country not long before that. I was one of them, and there were also some activists of the already existing organization for ties with Soviet Jews who had been refused the right to leave for Israel. With the help of donations from a number of individuals and organizations, we established centers of legal and psychological help for new repatriates and support for painters and actors, including the "Gesher" theatre. Then decision-making gradually shifted to Sharansky, and the role of Forum's presidium dropped drastically. I left the presidium.

My First Job in Israel

We realized that the main problem of our absorption in Israel was finding work. Two months after our coming to the absorption center, a representative of the Ministry of Absorption came there. She helped us to write our CVs for looking for jobs. When I wrote that I was looking for a job of a computer programmer, she said that this specialty was not needed in Israel and that I would find it very difficult to search out a job.

There was a special department in the Ministry of Absorption that was in charge of helping us to find jobs. We, on our part, read advertisements in the newspapers and spoke about possible jobs with Israelis whenever possible; we also gave them our CVs, just in case. In this way, after some months, Anya found work in a small private design and construction firm. She worked there for a short time only, because the owner passed away and the firm broke apart. In Jerusalem, there are only small private construction and design firms. They employ people when demand is high and sack them when business is slow. Anya worked in firms like these, and during the eighteen years of work before she retired, she changed four work places.

I had an additional line of looking for a job: every prisoner of Zion or a prominent Aliya activist could get help from one of the Knesset members or from another person who was prominent the country's economy. Ben Rabinovich, one of the distinguished Israeli managers, helped me, and it was at his recommendation that I was invited for an interview to the computer center of Bank ha-Poalim, one of the two largest banks in Israel. This center sent me to take a psychological test, which fortunately, could be done in English. After the test, they informed me that they were ready to employ me and invited me to another interview, in the personnel department.

When the personnel department official told me the sum of the would-be salary, I could not hide my surprise. In comparison with the allowance of the first months, this sum seemed to me fantastically large. The woman understood my surprise in an entirely different way and started talking about extras that would be added to the basic salary. The first benefit she mentioned was car expenses. When I said that I did not own a car, she consulted somebody on the telephone and said that I would get this extra pay even in the absence of a car. The same happened with the extras for telephone, which I did not have, and newspapers, to which I was not subscribed. I later found out that such formation of salary was called Israbluff, and it was quite popular in Israel. I liked all of it, but then she said that living in the region of Tel Aviv was a must for that job. She said, "We do not want an employee who has to travel 700 meters downhill, to sea level, and then uphill, on his way to work and back". This condition greatly upset my whole family and myself. We wanted to live in Jerusalem, but we also could not decline this first work offer, which was so good.

And again, we had luck. Just a couple of days later I was invited for a work interview to the computer department of the Ministry of Finance. Their conditions were nowhere near what the bank had offered, and in addition, they only agreed to employ me through a work force agency - that is, without making me a staff member and, accordingly, without any social security, but this job was in Jerusalem, and I gladly agreed.

I started work on May 1, 1988. During the first months, I would get so tired at work that I felt a lump in my throat. My experience in computer programming in the USSR consisted of a three-day training course and several months of work with the equipment that was a generation behind the equipment in Israel. Even working with a keyboard was new to me, and finding a letter on it took an unacceptably long time. At first, I wrote programs using other people's algorithms, but I gradually came to understand what the economists who used our systems needed, even when they could not express their needs, and sometimes before they realized these needs. Some months later, I received an assignment to work out a system totally on my own. After I completed a second system, and the economists who worked with these systems approved of it, I got several assistants - computer programmers who had also recently come from the USSR. The amount of work for my team was growing, and I was allowed to add some more people who had also come through work force agencies. By that time, more people were coming from the USSR, and there were many candidates for each vacancy. Choosing and refusing became a difficult problem for me, so I worked out formal criteria and selection tests, which reduced to a minimum the possibility of an arbitrary choice on my part. In two cases, I employed close friends without any tests - I knew that they were good specialists.

We made a good team. We met outside work, at family get-togethers and picnics. With time, most of the new projects in the ministry became our team's job. I remember an episode from that period. Once a year our department went on a two-day trip. At breakfast on one of these trips, I was sitting at the table with head of department and some other ministry employees. One of them suddenly asked, "Vladimir, why do you take only Russians for your projects?" I wanted to name some "native" Israelis who participated in our projects, but head of department answered before I had time to open my mouth: "Because Vladimir can make Russians work, but nobody can do it with you". This was certainly an exaggeration, but to some extent, did characterize the attitude to our team.

In the beginning of the eighties, Israel often saw strikes of state and trade union sectors against privatization, and workers of the Ministry participated in them. To the general demands of the strikes, they added a demand to dismiss workers who were employed through work force agencies - that is, us. We refused to join these strikes. On the days of the strikes, we would come to work very early, before the pickets seized control of the entrance, and refuse to leave the building. After one of these strikes, the Ministry's permanent employees started joining us at work, and gradually, the Ministry of Finance stopped participating in these strikes.

An Apartment in Israel

The next important problem was buying an apartment. Where did people get money for the purchase, how was it done and officially registered - we learned about all these things from bits and scraps of information that came from different, often contradicting each other sources. I wanted to make it clear as soon as possible. This was important, first of all, for my mother, who was suffering from lymphoma for several years and agreed to repatriate to Israel only after we settled here. Some officials told us that prisoners of Zion were in some way entitled to state-owned apartments. I wrote a letter to the Ministry of Absorption with a request to give me information about ways of purchasing an apartment that were open to us. Some time earlier Volodya Brodsky, also a prisoner of Zion, had written a letter like that. They promised us to give us an answer after two weeks, but we did not receive it even a month later. We went to the Ministry, to the minister's secretary, and demanded an answer. The only thing she could tell us was, "You have to wait." "We will wait here" - we said and entered the minister's empty room where we camped on the sofa. This was something that we could only afford during our first months in Israel, when we had not yet "cooled off" from the heat of struggle with Soviet authorities. It is anybody's guess why the ministry did not call the police or, at least, their own guard.

In a couple of hours we were told that the minister would not talk with us in the "captured" room, but would make an appointment with us a week later and then answer all our questions. We came to this appointment with our wives and, for moral and language support, with Sara Osatsky from kibbutz Ramot Menashe The minister confirmed that we were entitled to social housing. He also explained that the rent for these apartments increased with the growth of the family's income, and that this kind of housing was usually granted to families with problems, so that the condition of these apartments and the neighbors could be very special. On the other hand, he said that Australian Jews had donated money for helping prisoners of Zion, and if we bought an apartment in the private sector, we could get a gift of 10,000 American dollars. We decided to buy an apartment in the private sector. To purchase an apartment, we had to take from a bank a mortgage loan, which we, like all new repartees, could have at preferential terms. When we got jobs and were able to take this loan, we concentrated on buying an apartment.

In our first apartment in Israel, 1988.

|

We bought our first apartment in a Jerusalem neighborhood called Neve Yaakov. The apartments there were relatively inexpensive, since the road to the city center at that time went through a large and not always quiet Arab neighborhood. The following episode characterizes the residents of Neve Yaakov. When we moved there, the neighbors' girls came to meet Masha. They were very surprised when they found out in what school Masha learned. "Only idiots learn there, you have to do homework in this school", - they said and left in indignation.

When my mother came, we were able to take two mortgage loans in our two mothers' names, and buy a small apartment for Anya's mother in a neighboring building. We later sold that apartment and in this way, we were able to help our children in purchasing housing. My mother needed help, care and treatment, so she lived with us.

We lived in Neve Yaakov for twelve years. By the time we moved away, our two mothers had left this world, Borya and Masha had families of their own, and we decided to change this apartment for a smaller one, but in a more expensive neighborhood. We sold the Neve Yaakov apartment and bought another one, in Ramat Eshkol, another Jerusalem neighborhood. Masha's family later bought an apartment in Giv'a Tsarfatit, - not far from us. Some years later, Orthodox religious Jews started settling in Ramat Eshkol en masse. Our clothes, and sometimes our habits, like watching TV on Saturdays, differed from what the religious Jews in our neighborhood were used to. In the end, we decided to move to Giv'a Tsarfatit. We like our apartment - it is in a relatively quiet and convenient place, facing the Old City. We can see the windows of Masha's apartment from our windows. Borya lives within half an hour's drive from us, and we do not have to pass the center of the city on our way there. We hope that the presence of female students from Hebrew University, in shorts in the summer and pants in the winter, will prevent turning our neighborhood into an Orthodox religious place.

My Discovery of America and a Little Bit of Sweden

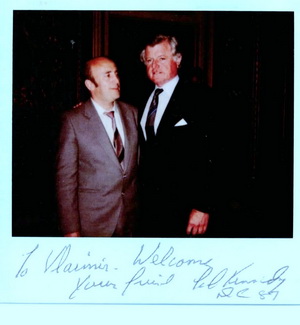

With Senator Edward (Ted) Kennedy.

|

A month after our arriving in Israel, Gorbachev and Reagan met in Washington. An American Jewish organization that was struggling for the right of Jews to leave the USSR, asked me to speak at meetings in a number of cities and towns of the USA. This was my first trip to the USA. Our absorption in Israel was just starting and we could never relax. They invited only me, without Anya, whose support could have greatly helped me. Refusing to go there was unthinkable, for the gate of the USSR was still locked. In a matter of days, I crossed the US several times. Every time I spoke at different meetings and conventions; in Washington I met senator Ted Kennedy and several congressmen. The tight schedule and the necessity of speaking English, sometimes with a number of people simultaneously, drained away my energy. My fatigue increased due to staying overnight in private houses, in a different place every day, without a chance of resting in privacy. There was a moment in Washington when I suddenly lost the sense of reality. I felt that I was in the camp in Kamchatka and all that all that was happening to me was in a dream. Fortunately, at that moment I had a phone call from Daniel Grossman, a former USA Assistant Consul in Leningrad, who had been kicked out of the USSR for helping refuseniks. He took in the situation at once, and took me to a cafe, where I gradually, with his help, returned to the reality, in the best of Russian traditional ways - that is, with talking and vodka.

My second trip to the USA took place a year later. It was improvised on the spot, fast and unexpected. It all started when Anya and I, together with other newly arrived refuseniks, were asked to accompany buses with American Jews who had come to see the conditions of absorption of Soviet Jews in Israel. One refusenik in each bus. In my bus, there were a group of about a dozen Jews from the USA and a representative of the Jewish Agency. All day long we were travelling around different absorption centers, and the Americans talked with the new repartees and listened to our commentaries and explanations. At the end of the day, the man who was heading the group came up to me and told me that their trip was a preparation to a fund raising campaign in the USA, for absorption of Soviet Jews. He said that four days later, their city would hold a very important convention for raising funds, and they wanted me to speak at that meeting. On the next day, they took me to the American Embassy in Tel Aviv, where a visa to the USA was immediately issued for me. In the evening, we were already flying to New York in a special plane that had brought all these groups to Israel. I do not remember the name of the city from which the group came; I only remember flying over America for three hours after the transfer in New York. The fund raising campaign was organized by paid workers of the local Jewish center, and it was headed by a volunteer, one of the most influential Jews of the city. I was supposed to speak on the second day after coming. They told me that it was a gathering of wealthy people, and everyone was expected to donate a minimum of 30,000 dollars. But I had no time to relax before that meeting.

The man who headed the campaign asked me to go with him to a rich old Jew who had long before retired and did not attend any rallies, but when he heard of my coming, he expressed a wish to see me. When we entered the house, the old man suddenly asked me in Russian if I knew some little town in Ukraine, but I had no notion of it. Then he asked about a nearby town, which I did not know either. He told me that after his bar mitzvah, but before the revolution of 1917, he, a young boy at that time, ran away from that town to America. No one in the family, his wife including, knew Russian. Suddenly she interrupted us and said to her husband, in English, with a heavy Yiddish accent: "Enough of this fooling around. You will go to this meeting tomorrow and give them money. I don't want those who now come to Israel to go through what we've been though in America. And let them go to Israel, they will become Jews and stay being Jewish there".

The next episode was in the morning of the day of the rally. The organizer of the campaign asked me to accompany him to one of the leading lawyers of the city. This was a Jew who had donated to different projects in Africa and even to Palestinians, but never to Israel, the organizer said. The minute we sat down in his elegant room, the lawyer started talking in harsh tones. He went into a long explanation of how he, as a Jew, felt ashamed for what Jews in Israel were doing to Arabs. I was unable to hold myself and interrupted his tirade with these words: "In the Soviet Union there is a real danger of pogroms now. It is very likely that Jewish blood will be spilled, and many of your Arab friends will be happy about it, - and what about you?" After a strained silence, we parted politely. Already in the car, I asked the head of the campaign how much harm I caused with my harsh question. He laughed and said that the lawyer suggested that they should meet and determine the sum of his donation.

After that, I went to the USA three times at the invitations of UJA, the most important Jewish organization of the USA. The conventions at which I spoke were of two kinds: meeting of big donors and mass meetings. The meetings of the first type were usually held in private homes, with fifteen to forty people present. After the speech of the community representative and my speech, every participant would stand up and say how much and why he or she meant to donate. They usually spoke about their parents, who had no place for escape from the advancing Nazism or about their difficulties in starting their life in the USA. Sometimes in the course of their story, they addressed me with remarks or questions. I liked the speech of one of the participants of a meeting like this in Pittsburg. He stood up and asked the audience, "Tell me, who of you after a Seder will go outside wearing a kippah (yarmulke)? Who of you does not have a small house or an apartment in Israel, just in case?" He finished with these words: "When we give to Israel, we donate to our own security".

Conventions of the second type were usually held in large halls of Reform synagogues. They consisted of speeches and group singing. Meetings of all these types included a buffet, coffee and tea. Nobody ever told me what I should say, but the time limit of the speech was always set and had to be observed strictly.

There were also some very interesting personal encounters. I was once spending a night in a private home, and the woman who was hosting me explained to me why so many American Jews wanted Soviet Jews to come to the USA. "Anti-Semitic views are strong with many Americans. These days it is unacceptable to show them, but they can burst out at any moment. Our generation is ready to this, because we remember our parents' stories of the anti-Semitism of the thirties. We are trying to stick together in our Reform communities, but our children find this boring. We knew that there, in the USSR, your Jewish identity was important for you and we hoped that when you come to the USA, you would join our communities and our children would follow suit". This did not happen, and the number of American Jews who supported the idea of Soviet Jews' going to Israel was growing. This tendency had a financial reason as well. I learned about it in San Diego in 1990. I was invited to a business brunch with the local community leaders, in which the aide of the Secretary of State for the problems of refuges participated. She explained that every refugee cost the state $46,000 on the average. The stream of Jews from the Soviet Union had grown sharply, while the government could not increase the allocations for them. "If you want more Jewish refugees, pay $46,000 to the state for each of them", - she said.

In the fall of 1989, the number of Jews who received permission to leave the USSR for Israel started to grow. Taking them to Israel became a problem, in the absence of direct flights. The countries where the transfer was possible limited the number of passengers and demanded a lot of money, ostensibly for their security, although the transfer points were guarded by Israeli security service. Christian Evangelists of Sweden and Finland decided to raise money for financing the repatriation of Soviet Jews via Finland. For raising funds, they organized a big rally in Stockholm. I was asked to speak at this event. I asked my religious colleagues in the Ministry of Finances, what the ultimate goal of these Christians was, and whether they engaged in converting Jews to Christianity. They explained that these people wanted to bring the second coming of Christ closer, which, according to their interpretation of the Bible, would happen when all Jews assemble in Israel. They did not engage in missionary work, since according to their convictions, it was Jews, and not converted Christians, who were to come together in Israel. They invited Anya and me to Stockholm and we gladly agreed.

The meeting was held in a huge hall with a large stage. On its side there was a platform with a cross drawn on it. The spokespersons were religious and political leaders, including the Chief Rabbi of Stockholm. I found it difficult to speak because of the cross, but I could not leave the platform, for that was where the microphone was standing. I felt relief when a representative of the Christian Embassy in Jerusalem took the floor. He started with expressing gratitude to Jews who agreed to speak from that platform. "For us the cross is a symbol of grace and forgiveness, while for them it is a symbol of pogroms and persecution", he said. The speeches were alternated with concert performances. I liked the ballet suite devoted to the fate of Soviet Jews and their struggle for leaving the USSR. In Stockholm, we met the woman who in 1986 brought to Leningrad the first professional TV team for coverage of the life of refuseniks. She found us and invited us to dinner. This was a very affluent Jewish family. In 1987, she took the risk of going to the USSR for shooting a film about refuseniks. She knew that for such "interference into internal affairs" she could be hit by an "accidental" car or got beaten up by "hoodlums". At the dinner she told us that when they were leaving the USSR, all the full films were taken away from them. They handed them in since these were only copies, while one of the tourists had already taken the original films to Sweden.

The Family Gets Larger

Grandson's circumcision.

|

The university studies did not go well with Borya. After the third year, he quit the university and enlisted in the army. He did not want to get the exemption from the army service to which he was entitled for health reasons. Since he came to the country at the age of 19, he was supposed to serve in the Israeli army for two and a half years. They took into account the year in the Soviet army, so he served in the IDF for a year and a half. Borya served in the artillery and went to all the hottest spots of that time: three months in Gaza, three months of military training in the Golan and three months in Lebanon, where he participated in Israeli military operation "Accountability" ("Din ve-Heshbon"). On his days off, he sometimes visited friends from our refusenik days. During one of these visits to the settlement of Kedumim, he met his future wife Dina. The wedding took place on June 1, 1993. The army transferred Borya, as a newlywed, to an army unit that was located near his house. This was a laboratory for repairing army computers, and it was there that Borya became a computer technician. After the army, he started working in this field. Thanks to his interest in computers and his talent for grasping new ideas, a couple of years later he already worked as a computer programmer. Borya has a good position with a big company. Almost every week he comes to us for dinner and a chat. Dina graduated from the university. She worked in a bank, then she completed a course in computers and for many years she has been working as a system analyzer in the management of banks' database. They live in Modiin, near Jerusalem, with their four children and Dina's mother.

Masha served in the Army after school and then entered the university to study pre-school psychology. In 1996, she married Misha. Misha works as a guide in Israel. They have four children. They live several yards off our place. I have written very briefly about Borya's and Masha's families, since I hope that sometime, even before they retire, they will write their own memoirs.

Talks on Economy

I had got to know Ester Karmi, an Israeli radio Russian reporter, before I saw her in person. When she learned that I had started working with the Ministry of Finance, she invited me to the studio to speak on Israeli economy in Russian. I later did it regularly, and these talks were useful for myself as well, because they were a challenge for me to read articles on economy in Hebrew. This broadened my horizon and sped up my learning of the professional language. I hope that my radio commentaries helped a little in the absorption of the big Aliya of the 90-s. The absence of basic knowledge of economy was a serious obstacle for these people. I will give an example. The Russian language newspapers stirred up a groundless fear of mortgage loans, which were linked to the price index. People were afraid of buying apartments. It took the new repatreates several years to form the understanding of Israeli economy that would enable them to overcome this fear. I hope that my Russian language talks on economy helped this process. When people realized the absurdity of their fear of mortgage loans, which the Russian language newspapers prompted, many families rushed to buy apartments, and the prices skyrocketed above the economically reasonable level. Many new immigrants bought their apartments in this period for unreasonably high prices. The prices went down a year later, but many families had already overpaid for the apartments they had bought.

After the Soviet Union fell apart, the countries of the former Soviet bloc started showing interest in Israeli experience. The Foreign Ministry of Israel arranged courses in Russian for specialists of different professions from these countries. I was asked to lecture on Israeli economy. My course usually lasted for eight to sixteen hours, depending on the group's specialty. I tried to build my lectures in interaction with the group, adjusting the material to the interests of the audience on the spot. This dialogue with the audience and talks with them during breaks allowed me to keep track of the processes in different parts of the former Soviet bloc. I saw at these lectures how the attitude of many listeners towards Israel changed. The pay for these lectures came in handy for the family.

In the middle of the nineties, I participated in the program for absorption of young people from the Soviet Union called "First home in Israel". This program was organized by the kibbutzim, and I gave talks on financial and economic absorption in Israel. I hope that these lectures helped young people to adjust to the new surroundings and to avoid mistakes. In the beginning of the 2000-s I stopped giving lectures in Israel.

Israel - Russia

We came to Israel when the USSR was undergoing significant changes, which Soviet authorities called "perestroika and democratization". Many Israelis were interested in what was happening in the USSR and asked us about it. They were, first of all, interested in the situation with the Jews. We told them that the state anti-Israeli propaganda, with its strong anti-Semitic flavor, had shrunk. It looked like the official limitations on accepting Jews for jobs and to universities had stopped. But non-officially, most of the managers tried to stick to them since they were sure that these limitations would come back. The democratization brought about an outburst of street anti-Semitism. Various societies, whose motto was "save Russia, beat the Jews", had mushroomed out of nowhere. In Moscow and other cities, meetings of the anti-Semitic society "Pamyat" (Memory) were held. My colleagues in the Ministry of Finance of Israel were interested in the economy of the USSR. People often asked me, "Is there enough [arable] land there? And water?" When I answered that there was plenty of both, the next question was "So why can't this country supply itself with food products?" In the beginning, I was somehow able to answer this question, but then I forgot why.

December 1, 1989 was a nerve-racking day in Israel's relations with the USSR. Israeli radio broadcast information from a Soviet airline that a Soviet plane with children hostages was heading to Israel. It caused great tension in Israel. First of all, - children. How to neutralize the terrorists without harming the children? Secondly, the plane might have been hijacked by Jews who wanted to break through to Israel. What should we do with them afterwards? Why was it an airline and not the government that contacted us? A large landing lot was freed for this aircraft in Ben Gurion, our only airport. Anti-terrorist forces were sent there and the Minister of Defense Rabin came there, too. The terrorists agreed to talk only with "the Boss". Rabin came up to the gangway. They offered him a million dollars for allowing them to fuel the plane and proceed to South Africa. At that time, the anti-terrorist unit broke into the plane and seized the terrorists. It turned out that there were no children in the plane and that the terrorists were tattooed drug addicts, criminals who thought that Israel was in Africa. Israel extradited the terrorists to the USSR, but the prerequisite for that was that the Soviets would not subject them to death penalty, which was a legal punishment in the USSR in those days. This incident helped to normalize the ties between the two countries - the process that was gradually gaining force.

Of the August 1991 coup d'etat in the USSR I heard when I came to work to the Ministry of Finance. Many workers of the Ministry asked me, "What is going to happen?" I answered that if the leaders of the coup seized power, a huge number of Jews would flee from the country. In that event, Israel would have to organize refugee camps in the bordering on the USSR countries, and then transport Jews from these camps to Israel. The reaction of Israelis to my prognosis was interesting. Some said that a distressing situation like this was sure to bring the Messiah. The more practical people said that in this case Israel would eventually make serious efforts at absorbing the new immigrants - for "we are known to be at our best when dealing with extreme situations".

In 1990 and 1991, 350,000 new olim came to Israel. Many settled in our neighborhood. At that time, there were few Russian-speaking workers in state offices, services and shops. We went with new immigrants to various offices and tried to explain to them how to solve everyday problems. At that time, many organizations for assisting the newcomers came into existence. We tried to find ways to establish contacts between these organizations and the new immigrants. Some of our relatives and friends had contacted us before they came, and we tried to find apartments for them in advance. In spite of the stressfulness of these days and the complaints of some of the repatreates like "for what have you brought us here" - we felt satisfaction because we were able to help people.

January 1991. A rocket attack alarm at the time of our 25th wedding anniversary celebration.

|

In January 1991, at the peak of the big wave of repatriation from the USSR, the war in the Persian Gulf broke out. The armies of the USA and several Arab countries were fighting to liberate Kuwait, which had been occupied by Iraq a few months earlier. Iraq shot rockets at Israel, trying to provoke Israel to take action against it. If Israel had retaliated, the Arab countries might have left the coalition with the USA and possibly, side with Iraq. Israel did not enter the war, but the everyday rocket bombings lasted for over one month. Israel feared that Iraq might be using chemical weapons, so everyone received gas masks, which they were obliged to carry with them at all times and don when alarm sirens sounded. Every apartment was supposed to have a hermetically sealed room - that is, a room where the windows would be sealed and curtained and the slots under doors stopped with rags. The family were to stay in this room during air raids. In those days, the new immigrants were immediately on arriving at the airport handed radios and gas masks. Radio broadcasts in Russian were organized.

With the mass repatriation from the USSR, and later from Russia, my fellow alumni and colleagues from work came to Israel - now we were able to renew our old friendships. I also made friends with other people who came from the USSR. For me, the negative consequence of the mass repatriation was my poor Hebrew. I never had much talent for language learning, and when this factor was combined with the opportunity to speak Russian most of the time, the result was that now, after 33 years in Israel, I feel ashamed of my Hebrew when I speak with my grandchildren.

In 2006, the Hebrew University invited me to lecture on the economy of Israel at the Oriental Studies faculty of the Moscow University. I gladly agreed and asked them to plan the course in such a way that would give me a week off, for going to St. Petersburg (Leningrad). Before applying for an exit visa to Israel, I often visited Moscow on business trips and knew the city very well. When I came to Moscow in 2006, that is, nineteen years after I had left the USSR, I did not feel that I came back to my birthplace - rather, that I was a tourist in a foreign city that I had often visited in the past. I usually lectured in the evenings, while in the daytime I walked, with a guidebook, around Moscow and went to museums.

Once, during one of these walks, I passed a large bookstore in downtown Moscow. In front of the store there were stalls with books. On one of these bookstalls, there were books on Judaism in Russian and Hebrew, and the stall next to it sold anti-Semitic literature. Both had a large choice of books. I decided to walk past this bookstore once more when I finished work. This time, there were fewer stalls there. One of them had books on Judaism, together with the anti-Semitic books. When the shop man saw my smile, he tried to justify himself: "Business first of all", - he said.

When Anya came, we spent a week in Saint Petersburg together. We walked around the city and saw places that reminded us of various events of our life. We met friends, tried to enter our schools, but we the doors were closed to us. The trip was very emotional, as if we looked into the past, but with the eyes of tourists.

Changing Places of Work

As years passed, I felt the dubious character of my position in the Ministry of Finance stronger. On the one hand, I was the manager of several projects simultaneously, on the other hand, - an employee of a fake company that was created exclusively for hiring workers for the computing department. I depended entirely on my boss's mood. Most of the time his attitude toward me was very good and he never missed a chance to praise me. However, when he felt that I was too self-confident, he deliberately pronounced my total lack of rights. From the professional point of view, the work in the Ministry of Finance was becoming less and less interesting. In 1995, after six years of work, I decided to try to find a job where I would enjoy all the rights of an employee and have interesting work prospects. I spoke about my plans with one of the leading workers of the Ministry with whom I had a very good personal and work relationship. He told me that at that very time the research department of Bank of Israel was looking for a specialist in informational and mathematical research software.

The employment conditions that Bank of Israel was offering and the work itself were very attractive. The management of the research department set a probationary period of three months for me; they suggested that instead of quitting my present job I could spend my yearly leave for work with them on an open schedule basis. At first, my boss at the Ministry admitted that there was a certain gap between my formal position and my actual job description and promised to transfer me to the staff of the Ministry. This would not only improve my employment conditions but also open new professional prospects for me. Some days later, he suddenly announced that there would be no changes. I later found out that he had spoken with the computing department of Bank of Israel and they told him that they were not planning to employ a Lifshits. He could not imagine that it was the research department that was ready to take me on.

I started work with the bank on March 1, 1996. Everything was new and unknown for me there. I liked what I was doing, for it demanded constant widening and deepening of my professional knowledge. Contacts with other workers of the department were interesting and satisfying. I took it upon myself not only to provide the bank's economists with algorithms and calculations that they needed for their research, but also to build a database that would be able to promptly adjust itself to the natural in research work changes of demands.

I Take Root in the Bank

At the end of my first year, the managers of the research department who had employed me left the bank. The new head of department said that the computing office objected to developing models and programs inside the research department, and that this was why he could not transfer me to a position of a permanent worker. Without this status, an employee could stay on the job for no more than three years. For a year I was looking for a new job - to no avail. This was a hard year. It is very difficult to find a more or less suitable job at fifty-six, and I reproached myself for irresponsibly leaving the Ministry of Finance, where I had a guaranteed job. After a year of searching, I received two job offers, almost simultaneously. One was with the computer department of Leumi Commercial bank, the other - as an administrator of the international crime database in police headquarters.

During the year of my job hunting the management of Bank of Israel department where I worked changed again. I talked to them and said that I liked the work in the bank, but I could not dismiss the job offers that I had received, so the only way out was to give notice before the maximal possible term of my work expired. It was already impossible for me to receive a position of a permanent worker, since in less than ten years I would reach retirement age. Two weeks later, the deputy head of department informed me that the management of the department and the bank wanted me to stay in the job. They offered me a special contract that would entitle me to all the rights of a bank employee while I worked, but no rights except the funded pension after retirement. I gladly accepted this offer.

In 2004, Israel adopted a law of gradual increase in retirement age. If this law had acted in 1997, when the management decided to let me stay in the bank, there would have been more than ten years left before my retirement age. In this case, I would have been able to receive the status of a permanent worker. I addressed the bank management with a request to consider the possibility of transferring me to a position of a permanent worker of the bank retroactively, from 1997. The consideration of my request took a year, since it was an unprecedented case and it demanded serious judicial and financial checking. In the end, the decision was positive, and I became a permanent worker retroactively. This change considerably improved my future retirement prospects.

According to Bank of Israel's rule, every worker who has reached the retirement age is obliged to retire. This is what I did, but the bank immediately signed a contract with me for continuing work as a temporary worker. I continued work on these conditions for five years.

Life Goes On

Anya and I in Sicily, 2019.

|

In 2013, I finished all my projects with Bank of Israel and quit work for good. I take care of our home, go to the swimming pool, manage my stock market investments and try to broaden my knowledge of history. Every year Anya and I go abroad several times. Anya retired when she was sixty-two and filled all her free time with her Granny's duties, which she enjoys. We have eight grandchildren - four in Borya's family and four in Masha's family. Borya's family live in Modiin, together with his mother-in-law, who has devoted her life entirely to her grandchildren and helping the family with household chores, so that we are just visiting grandparents there. Masha's family live some yards off our place, so Anya is a fulltime granny there and I try to do my best as a granddad.

2020, spring-summer,

Jerusalem

| <== Part 3 |