A Jew behind the Looking-Glass

Part 3.

Vladimir Lifshits

Translated from Russian

by Ilana Romanovsky

"Kresty" and Saving the Soviet Economy

In "Kresty" the attempts of the new Soviet administration to pull the Soviet economy out of the process of rolling down to the precipice were clearly visible. They started, like all the previous attempts, with reinforcing the discipline. This time it was the strife against theft and bribery among the management of the enterprises. This strife was entrusted to the most effective, from the Soviet point of view organ, the KGB. "Kresty" was overflowed with directors, chief engineers, and managers. I happened to meet and talk with some of them. In most cases of which I knew, the KGB used the same principle as the one they applied to us - the KGB did not seek the proof, but created it. I will write about a man who was brought into our cell. He looked absolutely confused, with fear in his eyes. It was evident that he had been arrested not long before, and that this was his first arrest and his first cell. He longed to talk with somebody, and he told me his story.

He had been a navigator in aviation and retired young. His wife never worked - she took care of their son, who had Down's syndrome. After retirement, he started to work as a manager of a number of gas stations. He described it as a very disgusting work. The cashiers at the station are usually women who were the dregs of society. They often drank and stole at work. He got fed up with it and went to work as a metal worker at a plant. Some time before the arrest he was called to the KGB, where they required of him to sign a paper that he had bribed the manager of the gas stations of the country's North-West region. He had not given bribes, but the KGB badly needed his statement. They explained to him that if the person who gave a bribe reports of it by himself, he is clear of criminal offence. The former navigator refused to slander another man. They let him go, but called him again in a week's time. This time they showed him statements of two of his former female workers who wrote that they had bribed him to give them an unpaid day off at the height of the season. He confirmed that he had sent them home at the season's height because they were dead drunk. They had not given him any bribes. This time the KGB explained to him that his choice was either to write a statement about the manager or to get behind the bars for systematically accepting bribes, and the minimal sentence was three years. They also made it clear to him that during the time of imprisonment he would be deprived of his pension, so that his wife and child would lose means of existence. He was unable to slander a man he did not know, and a result, he found himself in our cell. Since I had books of law, he asked me to compile a letter of complaint. I realized that this was useless, but I could not refuse him. We decided to do it in the evening, when the psychological state of the convicts demanded distraction. On the next day they took him away from the cell, probably moved to another one. This was not the first signal that our cell was bugged.

The work relationship between suppliers of goods, their sellers and buyers was mostly informal. The main principle of economy was "scratch my back and I'll scratch yours", and this included both theft and bribery. Toughening the strife against them led to total jamming of the economy. The authorities made a sharp turn in their policy. I later saw two posters with the Supreme Soviet of the USSR directives. One was about increasing responsibility for crimes in economy, the other about encouragement of initiative in economy. All these zigzags only aggravated the situation.

Moulding by Labor

The guarders of the regime must have disliked my behavior at the trial, so they sent me to the farthest from Leningrad camp, in Kamchatka. The transit from "Kresty" to the camp lasted about three months. It consisted of three days' trips from prison to prison. All the trips were identical. They loaded us into a prisoners' van in the prison's yard and took us up to a railway carriage. There, surrounded by armed soldiers with sheepdogs, we one by one jumped out of the car and immediately squatted, with hands on our heads. After the counting, we had to cram into the carriage quickly. Dogs on long leashes contributed to the speed of the operation. When reaching the destination, the process was reversed. The three-day duration of the transfers allowed the guards not to give us hot meals. For these days, we received a loaf of sour bread and three salted herrings. The herrings had to be declined at once, so as not to have problems with thirst and toilets during the trip.

The overwhelming majority of the convicts in common prisoners' camp where I got to was young thieves and hoodlums up to 25 years old, really repulsive guys. There was a special group for prisoners over forty. They lived in better conditions, they did cleaner work and they were not too often driven to do additional work in the evenings. If I had got to the camp as a common criminal, I would live with a group like this and would work in a warm place, at school, in an office or, best of all, near the kitchen. I would do homework for officers, many of whom took correspondence courses, I would teach especially respected prisoners English and for that, I would get good food and other benefits. But I had the ill luck to be the first and only political prisoner in Kamchatka for dozens of years. As the officers later told me, my appearance of a weak intellectual opened for them perspectives of promotion at work. For that, they only had to make me agree for public repentance of my crimes, using work overloads and pressure on the part of young criminals.

The Attitude of Criminals towards Jews

In "Kresty", if you are Jewish, it may add respect for you on the part of other convicts. They believe that a Jew will not be sentenced for a trifle. If he is behind the bars, it must be for something serious, and he himself is a serious person. This goes together with a harshly negative attitude to the Soviet power on the part of most prisoners. When on the 1st of May the demonstration passed under the prison's windows, shouts like "Beat the stinking Communists!", "Bolshevik bitches!" and so on were heard from the windows. The screamers were dragged out of their cells and put into the punishment cell, but the shouts did not stop. To the east of the Urals, however, the atmosphere in jails is different. With the movement to the east the Soviet patriotism of the convicts grows, and anti-Semitism grows with it.

I think that before meeting me, no one of the prisoners in the camp in Kamchatka had ever seen a live Jew, and if they saw one, they would not know that this was a Jew. But they had a very clear image of a Jew. First of all, all Jews were very rich. More than once they asked me to reveal to them where I hid my piggy bank. They clarified their request like this: I would not leave the camp alive anyway, and with the money, they would at least remember me. Secondly, Jews are omnipotent and ruthless. One of the inmates, with whom I was in the same "family", told me that at night prisoners who were known for their cooperation with the administration, woke him up and advised him to kick me out of the "family". "What do you think, when Jews come to power they will spare you because you supported Lifshits?" Several times I heard a very interesting version of Hitler's biography from different prisoners. Hitler, as it turned out, was Jewish. He came to power with the help of Jewish bankers and this was part of the plan of Jews to seize power in the whole world. But the Jewish bankers cheated him and because of that he later took revenge on all the Jews.

Talks with the Operative

The name of the boss of the operative department, or the oper, was Sergei Petrovich. From time to time he called me for talks. Part of these talks was evidently recorded on a tape recorder - this was felt in his reserved speech and also, sometimes, in the absence of logic in his questions. I remember two of these talks. In the first one he asked me if I had met Tyomkin. I answered that I could not know who of the prisoners that I saw in the camp was Tyomkin. Only he could know this, because he was constantly informed even of whom I stood next to at the hole in the latrine. Sergei Petrovich explained to me that Tyomkin was not a prisoner but a police colonel, head of all the camps and prisons of Kamchatka. To my perplexed question of how I could see him, bypassing the inner and the outer guard of the camp, he answered something like "Don't play the smart guy, just answer, did you see Colonel Tyomkin or you did not?" I later found out that Tyomkin was Jewish and they probably suspected that he was in conspiracy with me. Another time they suddenly took me away from unloading rolls with ice covered nets and took me to the TV room. On the TV they were airing a documentary about Bukhara Jews who had come to Israel and were now asking to be allowed to return. On the next day Sergei Petrovich asked me if the Soviet television was lying. I answered that it certainly wasn't, but then I added that I knew about 100 inmates of the camp. If on the next day the gates opened and everyone was allowed to go and be free, all of them would go, but I could give the names of at least five of them who on the day after that would ask to be taken back. Sergei Petrovich though a little and then told me to go. He even specified where, even though the address was not suitable for the tape recorder.

Sometimes we had less formal talks. One day he said that he knew for sure that I did not have any secret route of smuggling letters out of the camp. All my letters were checked by three people, one after another, before they were stamped "checked" and sent to the post office. So how was it possible that my wife knew all the details of the pressure they put upon me in camp?. I wished to him that his wife, after twenty years of marriage, would feel and understand his letters better than any watchful police officers. Then he forbade me to write to my wife anything about my life in camp. "The details of your life in camp can only be complaints, but you can only complain to head of camp". So in my next letter to Anya I wrote - I am forbidden to write anything about my life in camp, since this can only be complaints, but I can only complain to head of camp". The censorship let this letter be sent, too. Our talks were gradually becoming more open. In one of them he said that he was a Russian nationalist and therefore he hated Jews. I answered that my Jewish nationalism did not mean hate towards other nationalities.

A Request for Pardon

Representatives of public prosecutor's office sometimes came to the camp headquarters for receiving requests for conditional release. In January 1987 during the visit of representatives of the prosecutor's office, I was taken to the headquarters, not to the room where the representatives were sitting, but to the room of head of camp. There were two people in the room: head of camp and another man, who was called Kamchatka's prosecutor for penitentiary institutions. He asked if I had any complaints. I did not have complaints. The prosecutor said that I had an opportunity of being released ahead of time, but for that, I had to write a request for pardon. I said that I could not write a request like this because it implied confessing and repenting of a crime, while up to that moment nobody had clarified for me what my "known to be false" fabrications were. To my surprise, he said that repentance was not expected of me, it would be enough if I give my word not to break the criminal code in the future. He left without answering my remark that I had never broken it. I did not have a slightest doubt that nobody was going to liberate me and that the whole thing was a sheer provocation. If I refused, it would confirm my wish to stay in imprisonment and to disgrace the Soviet power by this. I had already heard statements like these. If I agreed, they would be able to distort my letter of request and present in as a confession of guilt. I had to win time, so I said that I had to discuss it with my wife first. The face of head of camp expressed great astonishment and fury simultaneously. I was offered freedom and I had the cheek to make conditions. The prosecutor took it calmly. He ordered to arrange a short meeting with my wife for me.

All the time preceding Anya's visit I was composing the text of this request in my mind. It was to be worded in such a way that it could not be used as a confession of guilt or repentance. It was to be short, so that Anya would be able to memorize it word for word. The meeting that was allowed to me was to take place through a glass window, so that the prisoner would not be able to hand anything to the visitor or even touch the visitor. The talk was on the telephone, so as to make monitoring and disconnecting easier. The visitor was forbidden to take with him or her paper and any writing tools. The visit was supposed to last fifteen minutes. At first we discussed family matters and only towards the end I told Anya about the request for pardon and repeated the text several times, asking Anya to convey it to our friends, for fear of possible distortions. Contrary to my apprehensions, they did not break the connection. Moreover, we received additional time for our talk. Some days after the meeting the prosecutor came to the camp again. I wrote a request and handed it to him.

A General Visits Me

After I handed in the letter of request the pressure on me became stronger. The member of my "family" who had been helping me to fulfil the high work norm was placed in the punishment cell. Every time when our camp barracks had to send somebody to evening or night works, the headquarters sent an order to include me into the list. They placed a formal reprimand in my personal file for leaving a pillow out of the center of the bed. I started being dizzy and having backaches, several times I was on the verge of fainting. Head of camp provoked convicts in my division by telling them that only Jews had the money for a wife to come for a short visit from Leningrad. Anya complained of what was happening in the camp to the Administration of Penitentiary Institutions in Moscow, but it did not change anything. Meanwhile, the atmosphere in the country started changing. Some political prisoners had already come back, and Ida Nudel [Ida Nudel was a refusenik and a Jewish activist who was sentenced to four years' exile in Siberia and later helped many Jewish prisoners and their families - translator's note] recommended Anya to get in contact with Kamchatka Regional Party Committee. Anya telegraphed them and wrote of serious discrepancy between my treatment in camp and the changes that were taking place in the country. The result surpassed all expectations.

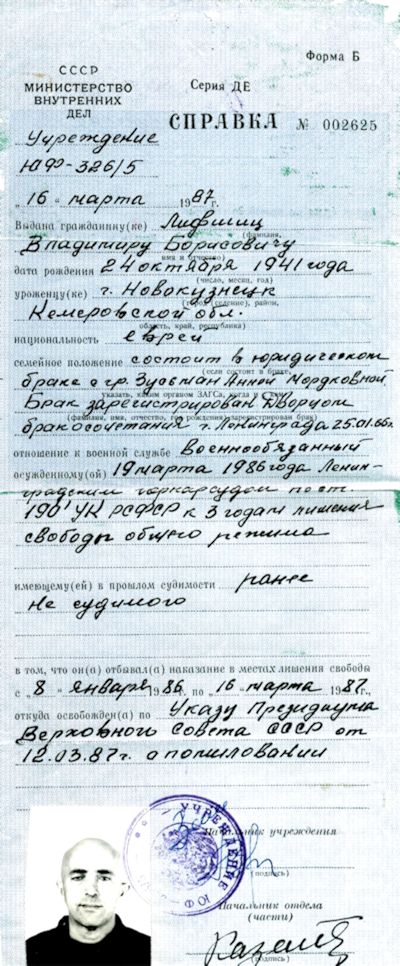

Certificate of Liberation, issued on March 16, 1987.

|

One day a messenger from the camp's headquarters ran to the industrial zone where we worked. He seemed to be astonished and shocked. "Lifshits, - he shouted - a general has come to you." He accompanied me to the headquarters, which was unusually empty. The head of the camp was waiting for me in the hall, and he inquired about my health with frightening politeness. The camp doctor's figure was visible at the end of the corridor. They took me to the room of head of the camp and left me together with a man of about forty years old, in a uniform of police general. He introduced himself as Kamchatka's police head. After that he asserted that nothing of what I said to him could harm me. I don't remember why, but I believed him, even though I had long before learned not to believe anybody. He had read Anya's telegram and said that he was informed about my treatment in camp. The only thing he did not understand was why Anya wrote about danger to life. I described to him our work on the previous day, when we carried logs with diameter larger than my height. Part of the way was down a steep hill, and we ran before a rolling log. Just at that time I felt that I might lose consciousness. Fortunately, that time it did not happen. I asked him straight forwardly if the offer of pardon was a provocation. He said that they were ordered to take away all the reprimands from my personal file. This was a sign of preparation for liberation. When it could happen, he did not know, because this issue was to be resolved at the highest level of authority. At the end the general asked what requests I had. I asked for two days off and to stop exacerbation of anti-Semitism in the camp. The two days he did promise. As to the second request, he said that there was no anti-Semitism in Kamchatka. He was right, in the sense that there was no state anti-Semitism. As an answer, I told him the version of Hitler's Jewish conspiracy. It was the first time during our talk when the general stumbled and was silent for several seconds; then he remarked that Hitler's nationality was a difficult question.

After the visit of the general my life in camp entirely changed. An hour after my return to work the camp doctor came to the work zone. This doctor always emphasized that he was first of all an officer and his goal was rectifying criminals. He often refused medical aid to prisoners with breaches of camp regime. I think it was his first visit to the work zone."Lifshits", he said - "my assistant says that your blood pressure is wobbling, come to the medical aid station." To go to the medical aid station I needed permits for crossing several inner camp borders. The doctor explained that I had the right of free movement within the camp. In the medical aid room, the doctor, without looking in my direction, prescribed two days of sick leave. They stopped sending me to additional work. Every self-respecting prisoner saw it as his duty to invite me to drink strong prison tea with him. In a couple of days they escorted me to the prison hospital.

The Liberation

Conditions in the hospital were lots better than in the camp. First of all, no work, no work zone, no evening or night duty. Secondly, free timetable - you could walk within the three hospital rooms or lie in your bed - whatever you wished. There was even a room with a TV set. Thirdly, the food was better and there was more of it. I was getting even more food than others. The hospital was near the camp for strict regime imprisonment, the inmates were serious people, and talking with them was interesting. This bliss lasted for almost a week. In the evening of March 14 1987, I was called to the room of officer on duty and informed that they had received an order of pardon for me. It was clarified to me that I could leave the camp any minute, but before next morning nobody could prepare a certificate of liberation for me, and without such a letter the first patrol of the many that acted in the city would arrest me. I agreed to stay until the morning. Naturally, I didn't sleep at night. I looked through my belongings and sent a message to my camp to tell them to whom they should give my shirt, my scarf and sweets. In the morning nobody called me anywhere. I talked to one of the officers and told him about the pardon. He promised to find out, but then he disappeared. I asked another one, and he disappeared, too. Then I started guessing that somebody found my return to Leningrad at the celebration of Purim very undesirable. To the last officer, who was the doctor, I gave a letter in which I had written that next time I would eat only after the liberation. The situation moved somehow only after I didn't come to the midday and evening meals. It looked like the administration begrudged the efforts they had made at feeding me. They returned me to my camp where they issued a liberation certificate, gave me the money that I had earned in camp, and also the money that Anya had sent in advance.

They assigned an officer to escort me until I leave Kamchatka. The officer told me that because of a snowstorm planes from Kamchatka were not flying for several days, and there were no buses to the airport. They had booked for me a room with a bath (!) in the best hotel in town where I could stay and wait for the weather to change. Before the liberation I wanted to stay for a day or two and see the Avacha bay and Nikolskaya Sopka and to buy the famous Kamchatka smoked fish. But now I decided firmly to leave the place immediately if the authorities were trying to keep me back. After arranging with the officer to meet in the hotel in the morning, I hitchhiked to the airport in trucks. The floor in the back of trucks was packed with people, but they moved aside before me. Nobody wished to deal with an elderly man in prison clothes.

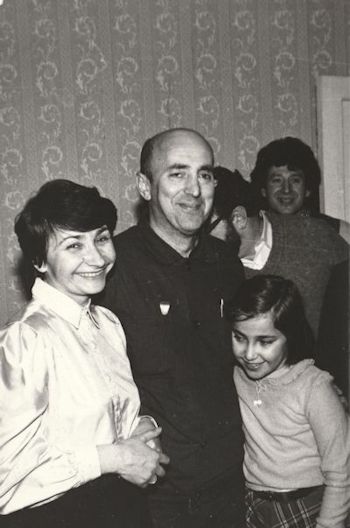

Back home. March 18, 1987.

|

The night at the airport was very fruitful: I managed to call home to Leningrad, enjoyed cold chicken in the buffet and settled it with the cashier on duty that the first air ticket to Moscow she would leave for me. In the morning a small miracle happened - the flight to Moscow, which had been delayed for several days, was allowed to take off. Since the highway from the city had not been cleared yet, and part of the passengers slept in the airport, after the check-in some seats remained unoccupied and the tickets were sold. The first ticket was mine.

I took the first daytime train to Leningrad from Moscow. A lot of people were meeting me at the railway station, and part of them went to our place. So many people squeezed into our apartment that Masha, who was twelve, tried to climb to the top of the wardrobe to see us and hear our talk.

After my liberation, Borya was taken to hospital. Anya and I went to him. After seeing Borya we went to the hospital's head doctor. To our questions about Borya's health and future, he answered that they were going to take all the tests on the next day and then decide if he could continue his army service. We decided to spend the night in the town in order to hear the results of the tests. The head doctor said that there was no need for it, because he could tell us the results of the future tests right away. At the end of April Borya came back home. He was demobilized ahead of time because of his health, and the certificate of demobilization stated that he was unfit for military service because of ulcerative disease. The date of diagnosing the disease was correct, that is, before he started service.

The seven months between my liberation and our leaving for Israel were very active. People were walking in and out of our always crowded apartment, which became an arena for Jewish celebrations, lectures and seminars that were attended by many people, both friends and strangers. This was the period when many refuseniks, who had earlier been afraid of any kind of activity, became involved in Jewish life. Some of the visitors were Jews who had not yet decided for themselves the question of leaving the USSR. Some came just to meet people, to socialize, some wanted advice.

Purimshpil in our apartment. The spectators.

|

There were many guests from abroad. Among them, there were representatives of Jewish and Christian organizations, state officials of different ranks, even the governor of one of American states. Foreign reporters came for interviews. We decided to meet everyone and to tell the whole truth, without thinking of possible repercussions. Two group demonstrations of refuseniks took place in Leningrad. The first of them was near the Smolny building [the seat of Leningrad Regional Party Committee - translator's note] before Borya's return. I participated in it only as a photographer. The second one took place at the building of Leningrad City Party Committee after the death, on the way to Israel, of Yuri Shpeizman, who had been denied the right to join his daughter in Israel, in spite of his critical health condition caused by cancer. Borya and I participated in this demonstration, together with other people. I gave my camera to Senya Borovinsky and asked him to take out the film before the police took away the camera. He managed to do it.

Our Dutch lawyer called and asked if I wanted him to continue to handle our family's case until our leaving for Israel. I certainly did. Later, when we met in person, he described to us such an episode: in the summer of 1987 Korotich, the editor of the Soviet magazine "Ogonyok", spoke to a group of Scandinavian intelligentsia. He spoke about the democratization in the USSR and at the end, he asked what questions his audience had. Our lawyer got up and told, in a nutshell, our story - how in the heyday of the democratization they put me in jail and then pardoned, without even explaining the nature of my crime. He then asked why our family was denied the right of emigrating to Israel. Korotich didn't like the question, but he promised to sort it out.

Refuseniks' demonstration in Isaakiyevskaya Square. June 10, 1987.

|

Happy End

Three times the Soviet authorities informed us about their permission for us to leave for Israel. The first time it was on the telephone, late in the evening before our trip to the International Book Fair in Moscow. A representative of the visas department said that our application had been considered and a positive resolution had been taken, but the documents were not ready yet. We had never heard of such preliminary phone calls. In a couple of minutes she called again and said that now there was no reason for us to go to Moscow. I answered that our trip was not connected with the refusal to emigrate, so that the permission did not cancel it. At that moment the voice in the telephone became severe and she warned me that in case of my participation in an illegal action the decision would be annulled. It turned out that she meant the meeting against the anti-Semitic activity of the newly organized association "Pamyat'". This meeting was banned by the authorities, while the meetings of "Pamyat'" were not. I already knew that the organizers had decided to hold a press conference in a private apartment instead of the meeting. The press conference was not an illegal action, but anyway, I was not among the organizers and did not plan to participate in it. The goal of our trip was the book fair, in which Israel was participating for the first time. The representative of Israel, who knew us by sight, said that they had brought a whole container of books for Soviet Jews. We took out packs of these books and left them in certain, picked in advance lockers at rail stations, from which they were dispersed throughout the whole country. We never found out if these actions were illegal, since none of us was detained.

When we came back from Moscow, the visas department called me again and they invited me to come to them next morning alone. I was very much afraid of some dirty trick on their part, like "we are letting you go, but without your son, who has just come back from the army". I decided in advance to refuse to go unless the whole family could go together. On the next day there was no reception in the visas department, but they let me in and at once took me to the office of head of department. He was there, together with a woman officer. Again I heard the same words "your application has been considered, the decision is positive, but the documents are not ready yet". Then I heard a question that astonished me: "Do you have any complaints against the visas department?" The answer was quite natural - "None, except the refusals". Head of department started assuring me that it was not them but other organs that took decisions about refusals. "But what about the refusals on the grounds of too distant kin and parents' objections for their adult children to leave the country?" I gave names of families that got refusals for reasons like these. The man said that they were working at that. That was the end of the meeting.

Some days later we were informed, on the telephone, that the documents were ready and our whole family could come to collect them. The documents were handed to us by the same officer who I had met in the office of head of department earlier. At the end, she said that everybody could go, but asked me to stay. Anya stayed with me. "Vladimir Borisovich", she addressed me very politely, - "before your first request to an exit visa you held a Ph.D. degree, you were head of laboratory, your family had a separate apartment [an apartment for one family, not shared with other people - translator's note]. What made you decide to go to Israel?" I did not know how to explain to this woman what it was like to be a Jew in the Soviet Union. She started offering me standard answers, like street anti-Semitism, discrimination at work. "Do you have a college degree?" - I asked. She answered - "Yes, police higher school". "Then you studied Lenin's papers on the outcome of the 1905 uprising. Lenin wrote in them that when Russian authorities had serious difficulties, they directed the wroth of the nation to Jews". The officer thanked us for the answer and said that if we had any difficulties with flight tickets, she would be glad to help us.

We receive a warm welcome at Ben Gurion Airport

|

They normally gave Jews who were leaving the country two to three months for packing and settling everything. We were honored with a permission to stay in the USSR up to half a year. Thanks to our friends' help, we managed to get ready in less than two months. On November 1 1987, we bordered a plane in Leningrad and, after a transit stop in Vein, reached Israel on the same day.

Summer and autumn of 2017,

Jerusalem

|