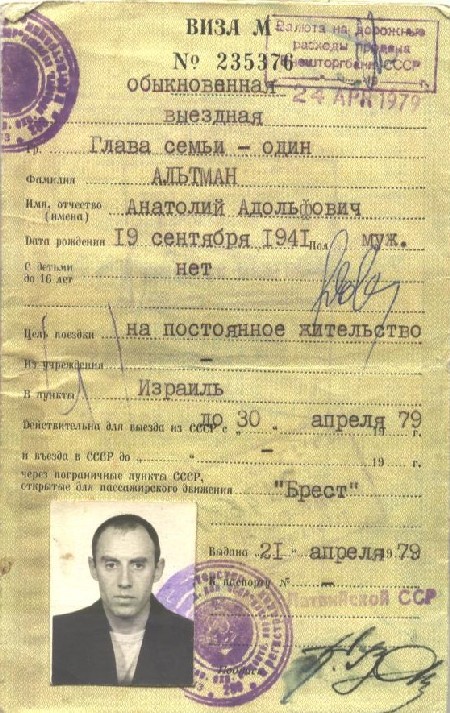

ORDINARY EXIT VISA

Anatoly Altman

Translated

from Russian

by Ilana Romanovsky

Part 1. Delayed Start

Excerpts from an uncompleted book

In

1967 in the far-away Middle East the thunder of shells died away,

planes and tanks calmed down, the dead were mourned for, "kadish"

was recited over the missing. All these things were somewhere over

there, where they were supposed to be, where there had always been

the line between the two worlds: the world of Isaak the firstborn,

endowed with all the sweetness and the bitterness of the right of

birth, and the world of Ismael the rebel, the one who was rejected by

the civilization of Abraham our forefather.

All

this was happening somewhere over there, while here, at home –

radio announcers and commentators covered the news and branded the

aggressors, milkmaids and steel founders expressed wrath –

naturally, “simple people’s”, and Jews – made up jokes about

Six Day War, as a sign of making peace with the condemners. Some time

passed, and everything returned to the routine of normal life. The

churning with the latest news of the tolchok

[Odessa’s

outdoor market – translator’s note] and

the Lanzheron beach Odessa would not take to heart anything that

could break the slow and lazy indulgence of the cool dachas in

Bolshoi Fontan [popular

Odessa seaside resort – translator’s note]

or, its antipode, the football fans’ fiery cut and thrust at

Sobornaya Square. In “bodegas” [beer

bars in the specific Odessa's argot

– translator’s note] the

foamy Schwab beer was poured from huge barrels into mugs and from

mugs into Odessa’s townsfolks’ hefty stomachs, accompanied by

“your health, buddy!” – “you too, bro, keep your head up for

me!” [These

toasts, as well as other Odessans’ talk examples, are in rich

Odessa’s argot, which is so well represented in “Odessa Stories”

by Isaak Babel – translator’s note].

They

did not see themselves as “Soviet comrades”. The Soviet power –

there still are some witnesses of that – flew into Odessa on the

wings of the revolution. It dispersed Moldavanka [a crime infested Odessa's suburb - see Isaak Babel once more – editor’s note] thugs from Odessa streets,

gave a good shake to the well-heeled burghers, declared

freedom for the people - and in exchange it appropriated, without

much ado, the banks, the production enterprises, the port and the

like – the spawn of capitalist thought. After that the dashing

cavalrymen dismounted, creamed off the finest buildings in town and

fenced themselves from the rest of the town dwellers behind

intimidating signboards UPR, DOPR, GLAV… , [

abbreviations for “upravleniye” – management, dom

prinuditel’nykh rabot – forced labor house, “glavnyi” –

main, central – translator’s note]

and so on. Then they calmed down and the townsfolk of the glorious

porto-franco

city of

Odessa returned to their routine life. Again, the former chic was no

longer there, but there still was, let us say, the larger-than-life stock of optimism and humor,

big enough to cover the whole of Deribasovskaya street, and

Odessans generously shared them with anyone who “knew a good thing when

they saw one”.

Sometimes

– and it usually happened in the loveliest seasons – that is,

spring and fall, the streets of Odessa (ah, Odessa streets!) - my

memory keeps it in its deepest hidden corners – powdered with

golden pollen, weary from the summer heat or scented with the

fragrance of freshly showered acacias that could drive you crazy when

in full bloom; - the streets and the lanes where I wandered paying no

heed to time or direction, the streets and lanes that were soaked

with a vague sensation of a near farewell – of which my Odessan

spiritual ancestor had in his own words sung with dashing bitterness:

“Ah, Odessa, I will never drink your wine again – oi wei - / Nor

sweep your pavements with my bell-bottomed trousers” [“Odessa-mama”

by Soviet poet Boris Smolensky, 1921-1941 – translator’s note]

would turn, by the will of the Great Sausage-Maker [an

allusion to “Envy” by Yuri Olesha, here – the Soviet leadership

– translator’s note]

into endless purple-grey bowels stuffed with swarming and bubbling

pulp, the pink foam above the surface of the peristaltically

convulsing stream jolted at the turns and near the numerous bodegas,

the flags and the sausage-makers’ portraits that had fallen down in

shapeless heaps, their otherworldly magnificence lost, they no longer

looked from their height with reproach and suspicion, and the mob,

which a few moments ago had formed a stiffly whipped homogeneous

mass, split into its components – male and female Odessans and

“baistryuki” – [the

brats or bastards – translator’s note],

future Odessans. [The

whole paragraph is a metaphoric description of May 1 and November 7

demonstrations – translator’s note.]

Sometimes

multi-colored and red dragons adorned with flags and banners would

fill the streets of the city; the leaders cast searching looks at the

swarms from the portraits above people’s heads; drums pounded,

waves of compressed air from huge pipes hit the crowd and, after

wavering a little, it reverberated with a roar in answer. The dragon

wriggled, lingered more and more often at numerous bodegas,

drowsiness started to overcome it until, weary from the warmth of the

lavish southern sun, it started to molt; its red scales, shed from

its bristly back, formed small jams. The standard-bearers would then

club together,

forming

classical Soviet-style triptychs [to

buy a bottle of vodka for the three of them – translator’s note].

I

was carried to Odessa in 1963, from a plain town on the periphery of

the world and very quickly I felt at home in this constantly

celebrating life city, adopted the local speech and behavior manner

and was ready, after some pushing and elbowing, to take my own place

in this Ukrainian-Jewish-steppe-sea Babylon. Odessa’s young people

were raised on the principles of tolerance, enterprise and

non-interference in the USSR’s internal affairs. And even though

the whole city was at our full disposal, we favored the city and

country beaches and Primorsky (seaside) boulevard. The necessity to

work for one’s living was seen as an irritating obstacle on the way

to the beach, and the minute you were through with all that, your

feet brought you to the sea as if on their own accord. At night, the

stretched above the city like a trampoline boulevard soaked up

thousands of burning hot bodies; the boulevard buzzed and vibrated,

the breeze from the sea caressed and fondled the most delicate in the

world knees and cheeks and believe me, when you are just over twenty,

it doesn’t matter a bit who these knees belong to or whose lips

consent. After drinking up all the joys of the boulevard the crowd

would swim away to Pushkinskaya and Deribasovskaya streets and settle

in ice-cream and coffee shops or pubs, and then, late at night, with

guitars or without them, sometimes after a slight brawl, one by one

or in friendly bunches, the young Odessans would disperse and scatter

to their own “ranches”.

My

“ranch” was in Moldavanka. I lived in a workers’ hostel as a

holder of a temporal residence permit to which I was entitled when I

got employed as a worker at a ship repair plant. Our life was simple:

a booze-up on the payday, sport, movies, books – that is, from the

point of view of loyalty to the authorities – no deviations.

Tomorrow or today – “ready for work and defense” (only explain

from who…). Sometimes guests would come, male or female, and the

ritual of making acquaintance and sharing a meal together started,

significant sounding toasts were pronounced, the ritual meal

progressed from one stage to the next, then came the stage of sorting

things out, and this was done either in the corridor or in bed. To

say that we never had enough money would be an understatement, and

maybe this was the reason why my roommates and I “knew a good thing

when we saw one” so well. I saw a lot in my life later, but how can

one forget the triumphal blooming of acacias, the aloofness of the

immortal Duc

[Statue of the Duc de Richelieu, Odessa's founder and first governor

- one of the its main symbols – translator’s note] awaiting

the Armada which is already hurrying to his help. I roamed the lanes

of the Fountain and old Odessa, smelling out, like a dog, something

that my soul was seeking but didn’t know its name, though as it

became clear later, the soul got everything it was looking for…

Years

later, at night, in the freezing isolation cell of Duc de Richeiieu,

sitting on the detached for the event of superior importance plank

bed, leaning against the slop-bucket, I received the report of the

Commander-in-Chief of the free squadron of Genoa’s merchants, the

rebel Geuzen, the fleeing pirates. The echo brought the news to the

farthest corner of the huge hall: “The holy city porto-franco

Odessa IS FREE, HURRAY, gentlemen!” But of course, you can see all

kinds of visions on the twelfth day in a penal isolation cell…

The

summer of 1967 found me working at a commercial enterprise that was

not exactly approved of by the law. I will quote an experienced

Odessan whose opinion was that “there ain’t no melukha

better than

this one, ya only need zekher”,

which roughly meant “there’s no government better than this one,

you only have to find the right approach”. In those years, among

other new ideas, there was a directive “from the above”: to open

workshops on collective farms. The idea was to use the agricultural

production waste and work force that had not yet joined the noble

impetus of productive labor (old people, invalids, alcoholics). It is

well known that ideas have to be pushed from the heights of pure mind

into the world of pragmatic implementation. And then something

indescribable started… The enterprising spirit of Odessans does not

need to be exemplified. But this was a totally different type of

enterprisers – they did not have to resort to “zekhers”

when the

“melukha”

itself

endowed them with accessories of authority like seals, forms, bank

accounts and the right to employ, evading all the ideological and

regime limitations, all kinds of “-shteins” and “-bergs”. And

the most important thing was that the authorities did not make you

face the problem of who to employ. A person’s morals, ethnicity,

social background and other decisive factors of questionnaires’

traps had no currency at that market. The main principle was this: “I

give you everything, you give me fifty per cent”. For example, if

the highest wages of a collective farm worker were 300 rubles a

month, this was my lawful salary, and even if I had to give half of

it to the “boss”, it was in those times not bad money anyway,

taken into consideration almost free meals, free bus rides and two

days off. Without class fight, without the directing role of the

Party we were quite happy on this classless post-ideological island.

The majority of these “greenhouses” staff were Jews, and even

though this was the reason for my landing in this company, to tell

the truth, my ethnic roots did not add any pride to my ego. The bus

would pick us up in the morning and after an unhurried ride along the

Black Sea steppe, it would bring us to the village. The ride only

took an hour and the morning drowsiness gave way to vivid discussions

of the latest news. I seldom joined discussions of this or that

football team, and talks about “who, when, where, how” did not

interest me either.

But

one day on the way to work in the morning I heard some almost unintelligible

rendering of the latest news, most probably, from one of “foreign

voices”. Palestine, air battles, Sinai, UNO, Arabs – both the

topics and the vocabulary were so far away from our everyday reality

that I didn’t ask any questions. Then from the Soviet sources it

became known that Israel was waging an aggressive war against its

peace-loving Arab neighbors. As I have mentioned before, most of us

were Jews and that is why the problem and its discussion acquired a

certain bias. The later coverage of the events in the Middle East

contained military events, commentaries, including historical

commentaries. It suddenly became clear that Israel’s population was

about three million people, while there were 100 million Arabs, all

in all. And when one day they spoke of encirclement, I didn’t hear

well and assumed that Israelis were surrounded, communications

severed and defeat was inevitable. But even though I sympathized with

the Israeli team, I was not too much upset by its supposed defeat –

we knew little about this country and personal feelings did not

project onto our attitude to Israel. That is, we knew that Israel was

populated by Jews, but they were different from us. After some days of

military actions and cheerful reports from the battlefields, there

was a certain change in the announcers’ voices – dramatic and

wrathful condemnations of the “aggressors” who thought too much

of themselves, with unfailing demands to bring them to account. Then

it became clear that the Israeli team was making it to the finals.

And Israel was not playing in hopeful defense – their air force

attacked and destroyed Egyptian airports, Israeli tanks were breaking

fronts and flanks and rushing to Cairo, the infantry and landing

troops were sweeping the trash that had been left by Jordanian

occupation of Jerusalem, the Golan heights were ours!

Since

when I started calling them ours – I don’t remember. Maybe when

the unfathomable, Biblical sounding names of Israeli statesmen and

military leaders: Alon, Ben Gurion, Shamir – were back-translated

and became Gurevich, Meerson and even Rabinovich, or maybe when I had

read “Exodus” and for the first time felt related to those who

fought for a national home and then, for the first time, my being

Jewish stopped tethering my feet. Israel fought there, but won here…!

At that time there was no Jewish home where that war did not lay

front lines between the old and the young generations. To lie low in

rough time, not to draw attention to oneself, to camouflage – the

ways which had been tested by numerous pogrom victims’ generations

– did not find the evolutionary continuation with my generation. On

the contrary, the wish to stick to one’s historical past, to

national identity demanded being different from the indistinguishable

social environment. Though some of us were already acquainted with

the dissident movement, and even earlier had lived through the

happiest in the world childhood without apparent losses – sure,

Stalin is thinking of us! – and then the perestroika speeches of

the next “father” ( the word “pakhan” – chieftain,

Godfather – I learned much later) about the previous “father”…

My

acquaintance with the movement that opposed the regime started with

meeting Avram, my new friend. By that time he had already served

about ten years in a prison camp and then, after being exiled to

Karaganda, settled in Odessa and started to do woodwork for a living.

This was what drew me to him, because since childhood I used to play

with clay and wood and make figurines and masks from them. Avram

attracted people, especially young ones, by his unusual views and way

of life. For example, the problem of God, which had already been

forever solved by someone for us, had further development for him,

and even with an attempt to question the solution which you thought

to be your own. Though actually, the problem never existed for us,

like its object, and Avram’s extravagancy in the “esoteric” and

“theosophical” questions we ascribed to his unusual biography. He

wore a tiny pin with Israeli flag, but even without that it was clear

where he belonged to, for his eyes and beard were out of place in the

Slavonic landscape. Avram did not eat meat or fish, drank water in

small gulps, practiced Hatha-Yoga and, with a screwed up face,

stoically endured the pain in his leg from a sore left by a poorly

healed old wound. The door of his house was open for everyone. Here

you could read “Exodus”, listen to a Geula Gil song on an old,

swinging like a dervish tape recorder, eat, chatter and daydream. His

camp friends came to see him, Zola Katz [victim

of political terror in the USSR – translator’s note],

may he rest in peace, among them; they drank and talked about their

life in camps. These retired old men recollected the rough times,

places of “business trips”, names of cops and cellmates. Avram

had mysteriously smuggled out of the camp manuscripts, poems by

banned poets and prisoners, notes on Oriental philosophy and

religion. Undoubtedly, all these things virtually intruded your mind

and turned upside down all “that school and family teach us”.

One

bright day he asked me what I thought about going to… Israel. Just

like that, you are going somewhere and somebody stops you and asks:

“Do you feel like going to Mars?” By that time I already wanted

to go, but how? I certainly could not seriously accept this

suggestion, but the situation was too dramatic to laugh it off, if

you didn’t want to hurt the person’s feelings. So Avram wrote

down my passport data and sometime in the autumn of 1968 a letter

from Israel was delivered to the address where I was registered. The

owner of the apartment – my uncle – was on good terms with me

though he did not approve of my way of life. When the letter came, my

family held a council and everyone wept “Woe!” As if it was not

enough for my uncle to worry constantly about the surplus square

meters in his apartment in the city center, to worry also about his

work at a button factory where he was accountable not only for grams,

but for carats and where cases of breaking work discipline had almost

ceased, to say nothing about financial discipline, and where the

whole staff had already undertaken to raise their work effectivity

towards the coming national holiday and to bring down the number of

immoral behavior cases in private life by 20 per cent! All this

seemed not to be enough for the wretched lot of my uncle, who

officially was a marketing department manager but who, in fact, was a

genius of financial underground, one of my numerous other tribesmen

who managed to unearth from fantastic, totally improbable places some

unbelievable valuables, but it was always done while looking around

in horror of another inspection, with trembling hands and shaking

feet – and in addition to all that, this small surprise, a product

of my nationalistic ambitions!

I

was holding the letter and could not really trust my senses; it

looked as if it had materialized from the world of wishes and would

slip away any minute. But the countenances of my relatives increased

my confidence in the reality of the letter – the stamp, the

postmark, the standard Russian text. It was signed by Kubernik Braina

from Petah Tikva, 32 Shprintsak street. Being my "cousin“",

she was addressing the government of the USSR with a request to allow

me to go to her with the aim of uniting our families; she also

volunteered to help me settle in my new place. My late uncle later

pointed out at the investigation that his attitude to my intentions

was utterly negative; to his honor, I must say that I do not remember

this. Most probably, he was just scared, both at the family council

and at the interrogation, and also between these events, before and

after. He did not do any wrong, may he rest in peace. He was only

scared. Fear, even in the light-minded atmosphere of a southern city,

came out of diabolic seeds that were forever planted in the

subconscious.

But

something had to be done with the visa, so I found out where the OVIR

[Visa and

Registration Department – translator’s note] was

situated, and with beating heart I went there. They explained to me

everything –to register the invitation I had to bring various

documents: a reference from work, the birth certificate, written

permission from my parents (I wonder if when they sent soldiers to

Afghanistan – another foreign country - they also asked their

mothers for their permission?). To tell the truth, I did not feel

determined enough to appear in the OVIR with the invitation, but

after several nights of fear (for some reason nights are the most

appropriate time to feel afraid) I gathered enough evil impudence,

and, as they would later say in court, stepped on the road of

treachery and Zionism. Well, the inner movements of your soul and the

doubtless rightness of your choice are one thing, but what

practically comes out of it after that is quite a different thing. It

is extremely hard and frightful to leave the linear movement path

that you were sometime, by somebody, ordered to take. What force will

push you away from this path if everyone is close to you, pressed

together and moving in an even senseless motion? And yet I dived into

this tar and every movement demanded tremendous effort. At best,

people saw me as an idiot, though not everyone. Aba Agapyan, the son

of a circus manager who had been sentenced to death and shot, blessed

me in a short and touching blessing.

Here

is a story from that time. I knew a medical student, a guy who was

born in a mixed family, his mother was Jewish, his father was from

the Caucasus and he was for a long time not in contact with the

family. His mother, a very attractive diminutive woman, married a

second time. Her new husband was a quartermaster service officer, a

Byelorussian who was some years younger than she was. I often came to

their house and I knew that the three of them were good friends

indeed. Valerka called his stepfather Lyosha, a pet name for his

first name Alexei, and the friends that came to see them were treated

with equal care and attention. I visited them soon after getting the

invitation from Israel and told them of my plans without concealing

anything. Valerka’s response was disapproving and skeptical, his

mother’s – somewhat nervous and frightened, but Alexei’s

reaction was harshly negative.

-

Just imagine, there’s a war, we are here, you are there. Will you

shoot at Valerka, at me?

I

could not deny myself the pleasure of noting that quartermaster

service was not supposed to be shot at. As to Valerka, I got mad:

-

Valerka is not a fool to go get shot for your ideals, he will get out

of it. And all the rest, those who come to me, that is, against me,

have to know what awaits them.

Some

months after that talk I met Alexei downtown. He rushed to my side

and from his first words I saw that he was fairly boozed. At that

moment he spat out a phrase that sounded as if it had been prepared

specially for me and kept for a long time:

-

Go away from here, you’re right, get out of this puke, everything

stinks here, they fuck up the best things…

After

that memorable evening I didn’t show up at their place, I didn’t

want to strain the relationship. Meanwhile Valerka got married, by

the day of the wedding his bride had got to an advanced stage of

pregnancy, and a week before that encounter she had given birth to a

son. Alexei, a young and robust man, suddenly became a granddad.

Everyone drank – officers and warrant officers, Russians and

non-Russians – how could it be different? A man had been born, so

many changes at once: the young people had become parents, their

parents had become grandparents, new feelings and duties, new roles

to play. All these things were seriously talked about, with drinks

and food. The zampolit

[Deputy Commander for Political Matters – translator’s note]

came when the celebration was at its height and asked what the

occasion was. Alexei filled a glass and handed it to the new guest:

“A grandson! Only yesterday we brought him home from the maternity

hospital – 4 kilos 200 grams!” The zampolit

smiled when

accepting the glass and said: “Well, well, congratulations! A great

event – a new little Yid has been born in Odessa!” Next second

Alexei gave him a slap in the face. The upshot came a few days later.

The zampolit

would not

sue Alexei in military tribunal and Alexei would resign his officer’s

position. The Officers’ Court of Honor (a phenomenon that hardly

fits into our everyday reality) gave this “Solomon’s judgement”,

and Solomon, as they say, was an old hand at solving Jewish problems.

Of course, this story can be explained in a simpler way – everyone

was fairly drunk and the zampolit

was too much

of a boor, but I think that the main factor was “little Yid”,

who, strictly speaking, was only a quarter Jewish. The hero of this

story – a Byelorussian, a demoted officer Alexei somehow linked his

slap in the face of the zampolit

with the

Middle East wars and our memorable talk acquired a most convincing

finale from unexpected quarters.

Meanwhile,

I started collecting documents that were needed for an exit visa.

Everyone already knows of course how references from workplace were

obtained. My dear fellow Jews, I received permission to leave the

country the day after handing an application in Riga’s OVIR (though

a day before that I had been released from imprisonment only a trifle

before my ten-year time was finished) and nobody demanded any

references. But don’t think that I do not know how you earned them

(papir und

noch papir) [paper and another paper – Yiddish – translator’s

note].

I

worked at a collective farm co-operative near Odessa, and my boss was

Jewish. Without burdening myself with unnecessary doubts concerning

the results of my request, I addressed him in a conspirator’s tone,

without beating around the bush, but somehow drifting into an

emotional tone. I talked about our love for this melukha

and how,

accordingly, it loved us, and how good it would be to live at home

and not to be “this nation”. And what do you think – he pressed

me to his breast melting into tears or may be

he gave me a

gift of half of my salary which I gave to him according to our

agreement? Oh, come on, you’ll say, it’s quite enough for him to

write this reference with an unmoved face and throw it to me as a

proof of having nothing in common with me. Like hell he did! His

whole body was shaking and he yelled in a choking voice about my

ungratefulness towards the Soviet people, the party, the

co-operative’s management and my coworkers. My escapades would not

lead me to any good (he was right here!), I had better have pity for

my parents. I don’t remember now how I stopped this fountain, but

it was clear that I could not count on my Jewish brethren, and I

decided to go to the village where the chairman of the collective

farm lived. It was December and the weather threatened to freeze both

your soul and your body. I got on a bus in Odessa and reached the

district center and there I got to a country road that led to the

village through the snow-covered steppe. I was wearing a coat that

was in vogue then but that was good only for the Deribassovskaya

promenade, and only if you entered into some cafes on the way to warm

yourself, and I was wearing no hat, as usual. While waiting in an

open space for a car to pick me up I started to freeze, at first only

nose and ears, then the cold penetrated inside. After making all the

movements to warm my body I realized that I couldn’t last long.

Another wave of shivering overcame me. The evening was coming. I

looked at the road and at the wilderness around me. The steppe was

magnificent, the evening shadows of rare trees were getting blue; the

steppe was smoothed by the winds, but the finest shades of pink

betrayed the rare raised places. Black birds were crossing the white

area hurrying to their hiding places for the night. I felt a stranger

in this splendid landscape, but the piercing cold did not allow my

mind to reach a more favorable state, and I started to call into my

consciousness the landscapes of Israel as described in “Exodus”

and “The Judean War”. While I was musing on such exciting

subjects a truck came near me. After running a dozen meters after it,

I asked the driver if he could take me to the village and he said

that he would first take a woman who was riding in the cab to another

village. I climbed onto the loading platform and sat on a wooden box.

The truck started and at first I held on to the side with my freezing

hands, for it was impossible to remain seated on the box otherwise. I

was thrown from side to side, standing up would be suicide, the

freezing wind was piercing through the coat, jacket and shirt,

burning my body and making me breathless, my uncovered head felt like

it was compressed by a stiff hoop that caused unbearable pain.

Sitting was equally impossible – the box jumped and leaped in its

own rhythm and then I took the only possible in this case position –

on my half bended but thoroughly frozen legs I hopped across the

endless Scythian steppe towards some unknown finish, almost oblivious

to the reason of my actions because of the terrible physical stress.

Only not to fall down, only to keep standing, otherwise you’ll just

fall apart. How long this terrible race lasted I cannot tell.

The

Chairman’s house was heated as hot as a furnace, he wasn’t in, but his

wife looked at me with compassion and offered food and drink to me. I

sat near the hot stove, chill waves were passing through my body and

leaving it, legs were aching, the heated blood hurt the tips of my

toes and fingers. I took off my shoes and tried to rub the stiff feet

that seemed to be falling to pieces. Soon the Chairman came; he was

wearing a short sheepskin coat and felt boots. He greeted me and

disappeared in the next room without saying a word. I got sleepy

while I waited, but he came at last and we started talking. I

explained what I wanted from him and it looked like he understood the

situation, at least he listened with attention and did not look

hypocritical. That evening a meeting of the management had been

planned, and he promised to discuss my request. I fell asleep the

minute when the Chairmen's wife made a bed for me. When I woke up

in the morning I found a note from the Chairman. It didn’t leave me

much hope, but after the long way there and a talk with a man who

intended to help me it was bitterly disappointing to go back with

nothing.

The

time for processing my application was almost coming to an end and I

had to do something about this bloody reference, to bring any kind of

an answer from work. But “the boss” refused point-blank to “have

anything to do with Zionist affairs” and I threatened him with the

law that obliged him to give me reference and said that I would go to

Public Prosecutor if he refused.

The

visit to Public Prosecutor ended like this:

-

We do not deal with your affairs.

-

What are “your affairs”?

-

Of the Motherland traitors!

-

What kind of a traitor am I? I am still a Soviet citizen!

-

You will be one! (How did they know everything in advance?)

The

skies of my beautiful Odessa ceased to be blue and cloudless, the sun

did not warm me, the wine gave no joy. I felt that I was falling ill

with the fever that all of us knew so well. It must be the morbidity of

my state that generated pictures of different, unusual sights of my

world. The city seemed to be surrounded by enemies who went into

hiding and at secret hours, under camouflage, went on forays on the

peaceful city, its streets and beaches. It was impossible to

understand what they wanted and even to identify them, and this made

it even more frightening. I saw vague shadows that dashed about here

and there, condensed into grey lumps and rolled into crowds of

careless people making them freeze for a moment, after which they

continued their way but they were already touched by the grey ashes

and did not even suspect it.

Diabolic

farce! Thus, cancer starts unnoticed - something, let’s call it

“pre-cancer”, creeps into a healthy body and without killing the

healthy cells forces madness on them and the cells forget their

function and start functioning according to the program that was

thrusted on them, moreover – they infect other, healthy cells with

the same madness! I am not sure that the thought that the cancer will

die when the living being dies gives consolation…

My

relations with friends and family started to rot. With great

difficulty and threats to do something drastic to myself I made

mother send me

Moscow met me with snow,

cordiality and contentment. I stayed at Avram’s daughter’s.

Behind us was the summer of 1968, a country house on the seashore.

Crabs were darting about on the deserted sandy beach. The wind in the

thicket of reeds was trying to keep count of something: “S-s-six,

s-s-seven, s-s-six”, but got confused and, without finishing, flew to

our backs and heads, stirred our hair and tickled our naked bodies

with light touches. It was probably there that the idea of organizing

a summer camp in Karolino-Bugaz [a

place on the sea shore not far from Odessa – translator’s note]

for young people from various cities of the country first came to

mind. Young Jews from Riga, Moscow, Kiev and Kishinev stayed in our

little house in Bugaz. This was another subject for discussion in

Moscow. One evening we went to David, a man we had heard a lot about

from Avram. He was another former prisoner who boldly and openly

displayed his attitude towards the Reds and opened his house to the

lucky ones who had obtained permission to leave the country. Everyone

went through his hospitable house.

I

remember the specific atmosphere and order, if the constant mess in

Khavkins’ place could be called so. People came, played Israeli

records, had coffee at two o’clock at night; on the wall there was

a map of Israel and a portrait of Moshe Dayan, on the table there was

a menorah, dictionaries, and all that in a “communal apartment”

[a communal

apartment is one where several families share bathroom and kitchen

facilities – translator’s note]

where anyone could see it. One day David found a cable that was going

to the attic, and there he unearthed some device. Half an hour later

two men rushed in and claimed the device. David refused to speak with

them. And then they started talking in almost human voices – this

gadget was state property, the bosses would flay them alive, give it

back, have pity! David poured out a handful of the remnants, that’s

enough for the report, you can remove it from the list of equipment.

David suggested that I should live in Moscow vicinity and work “for

our cause”. It looked like he couldn’t help me in the nearest

time, but if I worked for them it would be easier to strive for the visa. He

also suggested another thing – a convenience marriage in order to

leave with another family. With this I left Moscow, first to Lvov,

then to Chernovtsy. I lived at my mother’s, found an inconspicuous

job somewhere far away, but my friends came to me and I openly

visited them. I did not know that I had already been “scented”,

but meanwhile I did not see anything that could worry me (in any

case, during that period the investigation could not collect any

material against me). I lost hope to find a family that would be

ready to have me as their son-in-law and returned to Odessa. I had no

place to live and Avram gave me shelter in his rented apartment. The

rest of the summer was uneventful. Avram was preparing for a trip to

Moscow - he had been suffering from sharp pains in the legs, from the

war and prison camp time. Sometimes he would leap from bed in the

middle of a night and moan, unable to bear the pain. He was to

undergo examination and treatment by Moscow professors. We saw him

off at the railway station without knowing what was in store for him…

At

that time rumors appeared that in Riga, Moscow and other cities they

allowed to leave the country to those who had served time and their

families. Somebody came from Moscow and said that David Khavkin

obtained a visa in a rather unusual way… Goldberg, who had once

been the USA representative in the UN, arrived in Moscow. One of the

bystanders broke close to some government building, to the car where

the ambassador sat. The police and civilians with armbands were

pushing him aside, but in an unbelievable way, he managed to thrust a

letter into the car. At the same time, David was grabbed by the

collar and thrown outside, smashing his head, what a nuisance,

against the side of the car, in full view of the US representative

and other lovers of scandal. Naturally, the KGB people’s actions

should have been seen as aiming to protect the important guest. But

Goldberg was cheeky enough to neglect the hospitability and rudely

interfere into the USSR’s home affairs and bring the application to

its addressee. The Reds demonstrated their efficiency when they

processed the application and in a matter of a few days gave the Khavkins

permission to leave the country. Without losing time, David packed

his things and came to the famous Sheremetyevo airport several hours

before the takeoff, in accordance with the Aeroflot rules. In the

airport, after a more than thorough check-up, they took David and his

family to a special service room. There they took the couple apart

and made them undress for a “personal check-up”. The procedure

was nothing new to him – five years of prison camps teach you

things like these, too. The problem arose unexpectedly: Fira refused

to send away their little son from the “frisking room”. “Let

him look and remember, he won’t see things like these in any other

place!” The cops stubbornly insisted that the instruction demanded

separation of sexes. Time was running, the cops were frisking, the

plane flew away… The KGB men worked with great zeal, they were sure

that David would not fly “empty handed”, but the fact was that

they found absolutely nothing on him and, in their bewilderment, let

the family go home. David used the situation to see Avram in the

hospital and say good bye to him. On the next day they flew to

Vienna. But he did smuggle papers out of the country, and quite a

number of them. When arriving in Lod he chopped open, in full view of

all those present, an object that did not look suitable for

transporting documents and took out of it a lot of “compromising

material”. The local customs officials, though, listed this object as

an electrical appliance and in this way deprived the newcomer of the

right to buy electrical appliances at a reduced price. But that is

another story…

|