A Jew behind the Looking-Glass

Part 1.

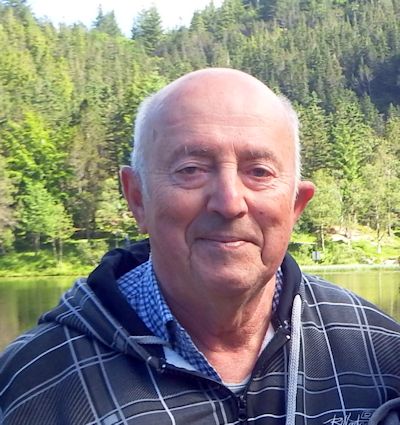

Vladimir Lifshits

Vladimir Lifshits, 2017.

|

Translated

from Russian

by Ilana Romanovsky

Let

Me Introduce Myself

My

name is Vladimir Lifshits. I was born on October 24, 1941 in the town

of Stalinsk (later Novokuznetsk), where my mother, Sarra Haimovna,

nee Markazen, was evacuated from Leningrad during its siege. My

father, Boris Haimovich Lifshits, volunteered to fight in World War

II in 1941, served as an officer in the artillery and was killed in

June 1944.

I

am starting to write this in 2017. The last 30 years my whole family

have been living in Israel. I am 76 and, like many people of my age,

I like to recollect stories from my life. Now I have decided to try

and write down some of them. When I say "to try", I mean it,

because I don't know how to write and don't like doing it.

Besides, what is written, solidifies, and even though I try to be

honest, recollections may always differ from reality, and I ask the

reader in advance to forgive me for that.

This

is not an autobiography, but a number of short stories of separate

episodes from my life that may be of interest to other people.

A

Jew behind the Looking-Glass

I

am a Jew. This fact has always influenced my life, in a different way

at different stages, but always. It also influenced these notes -

they are the notes of a Jew. Why in the looking-glass? Stand in front

of a mirror and look through it. You will see two worlds: the one

where you are standing, let's call it Pre-looking-glass, and the

one in the mirror - we will call it Behind the Looking-glass. There

are the same objects in both worlds: you and your reflection, the

furniture, the walls, etc., only their orientation is different. What

is on the right side in the pre-looking-glass, will be on the left

side behind the looking-glass, and vice versa. I lived in two worlds:

in the USSR and in Israel. Both have the same characteristic objects:

the state, the government, the court, the press and we, the citizens.

Everything looks alike, but the direction is different. In Israel we

are positive that all the state organs exist for us, to make our life

better and safer. The press helps us to see the government's

miscalculations and the courts prevent its despotism. In the USSR we,

the citizens, served the interests and the power of the state, the

press was supposed to enforce our commitment to the government and

the courts were supposed to serve its goals. I live in Israel, that

is why for me this is the pre-looking-glass, while the USSR is behind

the looking-glass. There cannot be a single and absolutely correct

choice for everyone, but the situation in which man is denied the

opportunity of choice is also totally wrong.

How

Anti-Semitism Helped Me

My

youth fell on the Thaw in the USSR. Starting from 1955, bans were

gradually lifted from many authors that interested me - Ilf and

Petrov (who were co-authors), Yesenin, Feuchtwanger and many others.

In the new literature things were less straightforward and more

interesting. The loathsomeness and horror of the inflated by the

state anti-Semitism of the end of Stalin's epoch was well behind

while the chronic Soviet anti-Semitism was perceived as the given

life conditions.

At

school I was, to put it mildly, not a brilliant student. In Russian,

German and sport my grades floated between "fair" and "almost

good". I was much better at Literature and History, and considered

myself almost a prodigy in Mathematics and Physics. Until I was

fifteen, I thought that I could effortlessly solve any problem in

these subjects. At fifteen I participated in Leningrad Mathematical

Olympics, and there I started re-evaluating my abilities. At the

Olympics I shared the third place with other participants and, as a

result, was admitted to the club of Mathematical Olympics winners at

the faculty of Mathematics and Mechanics (Mat-Mech) of the Leningrad

University. Learning there was very interesting, though I was not the

most talented student there and problems that were difficult for me

abounded there. When we reached the last grade, we were quite frankly

informed that all of us would be admitted to the faculty of

Mathematics except Jews. This exception had a fairly understandable

and logical explanation: in the previous year they admitted too many

Jews.

I

had to look for a technical Institute [an

educational establishment that awards degrees to its students -

translator's note].

The criteria I used for choosing one were the standard of teaching,

perspectives of an interesting job and a certain degree of

flexibility in nationality-oriented selection of students. I picked

the Leningrad Institute of Precise Mechanics and Optics (LITMO). The

competition for entering was high, but I wanted to be admitted very

much and worked hard to pass the entrance examinations. The first

time that I wrote a composition without spelling mistakes was at the

school leaving examinations, the second time - at the entrance

examinations. Fortunately, there was no exam in a foreign language. I

was admitted.

Now,

years later, I see the fact that I did not enter the university as my

luck. I would have made a mediocre mathematician, and to be a

second-rate mathematician is lots worse than to be a run-of-the-mill

engineer.

After

graduating from the LITMO I enrolled in a correspondence course of

the Faculty of Mathematics and Mechanics of the Leningrad University.

This combination of two degrees made me a rare specialist and

"compensated", to some extent, for my Jewish origin.

A

Student in the Years of Thaw

Students are gathering potato in a

kolkhoz. The author is in the center, to the right is Yakov Khodorkovsky (who is mentioned also below)

|

I

studied in LITMO from September 1958 until December 1963. During my

first year a conference of the Komsomol [Young

Communist League - translator's note] was

held there, but I didn't attend it. On the next day a student from

our gang came up to me and told me that now we were guarantied

tickets to all the students' parties, because there was "our man"

in the Institute's Komsomol committee. To my question if this man

could be relied upon in this matter he answered in the affirmative,

since this man was I. Thinking of the tickets for the parties, the

guys recommended me as a candidate. I was not present at the

conference, and since nobody knew anything bad about me yet, I was

elected.

At

the first meeting of the committee I found out that most of its

members were great guys, and green novices in Komsomol activity. We

had no political or ideological aspirations. I do not remember any

ideological activity during all my years in LITMO. As Komsomol

committee's members, we strove to do something useful for students,

to make their life more interesting. We organized students' parties

and concerts in villages in Leningrad province. Apart from September

kolkhoz trips [students

were supposed to do agricultural work on collective farms before the

academic year started - translator's note], there

was summer construction work in villages, and Komsomol played a

substantial part in arranging these trips. This work had been

obligatory before our time, but towards the end of our committee's

activity, it became voluntary. Sometimes we had to defend students

[from the administration], but I will tell about it later. At that

time it seemed a natural thing to do, but I later realized that such

humane approach on the part of the Institute's Komsomol committee

was possible only during the Thaw.

We

Violate Human Rights

At

the beginning of my work with the committee I was in charge of the

academic progress. For me, a freshman, it was evident that the first

problem was a large dropout of students during the first two years.

Most students who were expelled for poor academic results simply

neglected their studies until it was impossible to catch up. In many

cases the reason was the transition from the school system with its

everyday homework and frequent tests to the university style of work

where everything could be postponed till the next exams. We arranged

it with the dean's office that they would give us lists of students

who were supposed to be expelled and we would try to help these

students. We organized active groups of students with good grades and

called every would-be dropout to talks with these groups. If there

was an objective problem for poor academic progress, we organized

help. If the students didn't need any special help, we brought

pressure to bear on them. We photographed these students and hung the

shots on a board with the inscription "Candidates for Expulsion"

next to the assembly hall. Now I realize that this billboard was a

rude violation of human rights. We didn't know it then, but as a

matter of fact, this shock therapy helped many students.

The

Wandering Files

In

the episode I now want to tell you about the role of the committee

was totally passive, we simply knew about it more than other students

did.

At

the end of August, between my first and my second year in the

Institute, I was on duty as a committee member and it was my

responsibility to stay in the committee's room every day and

attempt to solve the arising problems. One day, as I was passing

through the entrance hall, I saw the lists of the newly admitted

students and near them there was a small group of people lively

discussing something around a young man, probably Jewish, who looked

very confused. Out of curiosity I came up to them and found out that

this boy had passed the entrance exams with better grades than it was

necessary for being admitted; nevertheless, his name did not appear

on the list. I took the lad to the committee's room and phoned Gena

Gromov, the secretary of the committee who represented it in the

applicants selection commission. Gena remembered this young man's

name and remembered his being admitted. "Keep him there, I'll

come right away and sort these things out", - he said. When he

came, he checked the lists another time and went to the rector, who

was the chairperson of the committee. When he returned, he assured

the boy that this was a bureaucratic mistake and that he was

admitted.

When

everyone left Gena told me what had happened. The Human Resources

department opened a personal file for each applicant, with their

first and last names and nationality (ethnicity) on the cover. All

the rest of the papers, including their grades at the entrance

examinations, were kept inside the file. After considering each

applicant, the commission placed the files of those who were admitted

and of those who were declined in two separate piles. When the

commission finished the sitting, the head of Human Resources stayed

there to draw up the report, and she concluded that the Institute had

admitted too many Jews. Without paying much heed to the contents, she

simply moved some "Jewish" files from the "admitted" into the

"rejected" pile, and the same number of "non-Jewish" files

travelled in the opposite direction - to the "admitted". To her

bad luck, one of the files that were moved into the "rejected"

pile contained the documents of a girl who not only had passed the

entrance examinations with good grades, but had also come to LITMO on

a recommendation from the Communist Party Central Committee of one of

the Baltic republics. This girl's parents had been prominent

communists who had been shot to death by the Nazis during the war.

She grew up in a party pension and was used to seek help in high

party organs. When she did not see her name on the list of those

admitted, she went to the party regional committee and secured a

reception with one of the secretaries. After listening to her, the

secretary called the Rector, and the girl heard many Russian words

that were new for her. In the end they decided to admit all the

applicants from the stray files as candidate students with all

student rights, and give them full student status when students with

low grades were expelled.

The

First Visit to the Synagogue

This

episode was neatly covered by Yasha Khodorkovsky in his story "The

Komsomol Patrol", which was published in an on-line magazine

http://berkovich-zametki.com/2009/Zametki/Nomer16/Hodorkovsky1.php.

I only want to try and add to his story some details that I find

interesting and I think I remembered them better than he did.

Gena

Gromov caught me in the Institute and asked me how soon the Passover

was going to come. The question was so unexpected that I responded

with a silly question asking if he needed matsos.

Gena explained that he didn't need matsos, but somebody had set

fire to the Moscow Jewish cemetery synagogue. Do we need it? To

prevent compromising provocations of this kind it was decided to

organize patrols of Jewish students who were Komsomol members in the

synagogue. Every day another institute was to keep guard. I was

appointed head of the LITMO group. Gena and I worked out the members'

list, and he asked not to tell anything to anybody because they would

call us to the party bureau room and explain all of it.

I

was a little late to the party bureau meeting, the group had already

assembled and everyone looked very tense. A call to the party bureau

boded no good for a student, and when they looked around and saw that

only Jews had been called, their optimism didn't fly any higher.

The finishing stroke to this picture was the coming of a man who

introduced himself to the party bureau secretary as a KGB officer.

The tension dropped when the KGB man explained our goal. By no means

were we the Neighborhood Watch, just praying Jews. Our goal was to

stop any attempts by drunks or hoodlums to start riots inside the

synagogue or in its yard. We were also supposed to cut short attempts

of passing letters to foreigners. This task we saw as something

impossible to carry out. How could we know who was a foreigner if

everyone spoke Yiddish? When everyone left, the KGB representative

told me that our job was only to take the hoodlum up to the synagogue

yard's gate, and after that their people, who would be sitting in

"Fish" and "Bread" trucks in gateways opposite the synagogue,

would take care of him.

Before

starting our guard we assembled at Teatralnaya Square and found out

that some of the guys were not wearing a headdress. They had to go

home to get caps and they came to the synagogue later. On the next

day I met the KGB man, and he praised our "professionalism" -

that we entered the synagogue in small groups and not everyone at

once.

In

my childhood, I would sometimes drop in into the synagogue for a

couple of minutes, out of curiosity. When I was a student, I used to

come to the synagogue yard every year for the Simchat Tora

celebration. Many Jewish young people used to gather there, some

sang, some danced and everyone drank. On the day of our watch I spent

a whole evening in the synagogue and heard the reading of the Tora

for the first time. I think that for most people in our group it was

their first visit to the synagogue.

The

Illicit Enthusiasm

The

Thaw is first of all broadening of the borders of permitted

initiative. Any breaking away out of these borders was severally

punished, even if the exit had a patriotic, pro-Soviet character. I

got convinced of this from my own experience connected with the

flight of Gagarin. The report of this flight brought me into an

ecstasy of pride and delight. The pride for the humankind, for my

country, for our science, for my own belonging to all of that. I ran

at once to the Komsomol Committee, where students were already

writing posters for a demonstration, which the Komsomol Committees of

different institutes had already arranged by telephone. The slogans

were something like "Hurray for Gagarin!", "Long Live the Soviet

Science!", "LITMO to Outer Space!" and so on. When we reached

Dvortsovaya Square, crowds of young people had already surrounded the

Alexander Column. They held posters of the kind that we had written,

and the same slogans could be heard from different parts of the

crowd. Then a young man with a loudspeaker mounted the steps of the

column. He said that he was representing the city Komsomol Committee

and congratulated everyone on the flight of Gagarin. Then he demanded

that everyone disperse because we would celebrate the flight at the

square at night. Nobody wanted to leave. A rumor spread that the

University was demonstrating, headed by the Rector. Everyone went to

the University along the Dvortsovy Bridge. We walked along the

carriageway trying not to get in the way of the traffic. It turned

out that the University meeting was over and its students joined us.

The column turned and headed back, to Nevsky prospect. Everything was

happening spontaneously, without any leaders or organizers.

After

passing the Arch of the Headquarters, we saw that the passage to

Nevsky was blocked by police cars and policemen with clubs. The front

rows stopped but the back rows pressed. I pictured to myself what was

going to happen and got frightened. One of the students leaped out of

the column to the left, waved his hands and shouted: "Go to the

Field of Mars Square!" Some people joined him, including myself.

The middle rows turned towards the Field of Mars, the rest followed

them. There were no clashes with the police. We came up to the

Eternal Fire, stood there a little, sang some students' songs and

then dispersed. I came to Dvortsovaya Square at night, but there was

no celebration there. The official celebration was held only a few

days later, when Gagarin came to Moscow.

On

the next day after our procession the Deputy Rector for academic work

called me and informed me that I was expelled from the Institute for

organizing an illegal student demonstration and that criminal charges

were brought against me and some other lawbreakers for damaging cars

that were parked along the streets. I was horrified. Expulsion from

the Institute automatically meant recruitment to the Navy as a seaman

for three years. Moreover, this formulation of the reason for

dismissing me excluded any chance of entering a school of higher

learning in the future. The lawsuit will undoubtedly end up in a huge

fine, which it will take a lifetime to pay. How could I tell Mother

about it? It was so horrible and frightening that for a long time I

was aimlessly hanging around in the Institute's corridors when,

unexpectedly, I was told that the Party Bureau Secretary was looking

for me. Actually, there was no reason to go there, but I went there

automatically. He met me smiling and said that the order for my

expulsion was cancelled and there would be no lawsuit. I was

flabbergasted and convinced that I misunderstood him. Then he showed

me one of the national newspapers. There was a full-page article

about our demonstration that was admiring the patriotism of the

students. Everything ended well, but an unpleasant aftertaste, an ill

feeling towards the system lingered.

I am during our practical training

at a Navy ship.

|

This

Is Already Serious

The

most serious test for our committee was "The Seamen's Case".

Male students of LITMO were exempt from the Army or Navy service as

common soldiers or seamen. Because the Institute had a Military

Training Department, we got military training while learning in the

Institute and obtained the ranks of junior lieutenants of reserve. In

the framework of this course we were supposed to do a month's

practice on warships of the North Navy as seamen. All the students

were split into groups of ten to twelve people and each group was

allocated to one of the ships. "The Seamen's Case" happened to

students who were a year ahead of me in their studies. The groups for

the military service course were composed in such a way that in one

of the groups out of ten people eight were Jews. This group happened

to get to the ship whose commander announced from the start that he

did not like Jews, and later did everything in his power to make

their service not just difficult, but simply unbearable. For example,

after the exhausting sea trips he would send the students to clean

the not yet cooled boilers.

An

officer, the representative of LITMO in charge of the sea practice,

was informed of the abnormal atmosphere on the ship. He decided to

talk to the students away from the ship and for that goal arranged a

lecture for them in a school class. In the morning the students were

lined up and ordered to go to classes in formation and return to the

ship by one o'clock. When they came to the classes they found out

that there was no light there. The LITMO officer commanded them to go

back to the ship. On the way back the boys decided that since they

were expected on the ship only at one, they could meanwhile take it

easy in some cozy place on the shore. The electricity in the classes

was soon restored, and the LITMO officer went to the ship for the

students. When it turned out that the students never reached the

ship, the officer offered to find them and bring them back to school.

Instead of that, the ship commander put the whole base on the alert

in connection with "the desertion of a group of seamen". The

patrols soon found the students and brought them to the ship. All the

students of this group returned from the sea practice with references

saying "can not be an officer of the Soviet army".

The

incident at the military sea practice put the administration of the

Institute in a difficult and unpleasant situation. On the one hand, a

student who had demonstrated his incapability of being an officer had

to be expelled from the Institute. On the other hand, the biased

attitude towards the students was evident. The state anti-Semitism

did exist in the USSR, but displays of individual anti-Semitism were

not encouraged. The management of the Institute decided that first of

all these students should be expelled from Komsomol. An expulsion

like this was enough to throw a student away from an Institute. But

at that point a flop happened that the administration did not

foresee. The Komsomol committee decided to issue a reprimand to these

students for breaking the service regulations and failure to carry

out the officer's command, but not to expel anyone from the

Komsomol.

According

to the Komsomol's statute, the last authority that can take a

decision on admitting or expelling members is a committee with the

rights of a district committee, and our committee had these rights.

No authority could change our resolution, so they started putting

pressure on us. The party committee of the Institute adopted a

resolution to recommend us to revise our decision, turning it towards

expulsion. Two committee members, who were communists, voted for the

expulsion, but the majority was still against it. They called us one

by one to the party committee and to the city and regional Komsomol

committees. They explained to us and tried to convince us that this

lack of subordination and deviation from the party line could harm us

in the future. We were already feeling by ourselves that the Thaw was

nearing the end and that the age of strict submission was coming. I

think that if the issue did not concern the fate of specific people,

students like ourselves, we would have given in. But in this concrete

case the committee stood up to it.

The

Personal Final Score of the Thaw

When

the term of office of our committee ended, all its members, including

myself, decided to quit community service. As it was acceptable to

do, we prepared recommendations for the Institute's Komsomol

conference about the candidates for the new committee. In the morning

on the day of the conference the city party committee sent a

directive to cancel it. The conference took place a few days later,

and different candidates were recommended by the Institute party

committee and the city Komsomol committee. Many years later I

happened to meet the student who had been elected secretary of the

new committee. He was making a party career and complained to me that

the Jewish nationality of his wife was a serious obstacle. Divorces

were not approved of in those circles either, so the only thing I

could advise him to do was to kill her.

All

our hopes for development of real democracy, pluralism and personal

freedom in the USSR turned out to be an illusion. Nevertheless, I do

not consider my Komsomol activity useless. We managed to help

specific people in given conditions. Besides, it was useful training.

After retiring, when I had some spare time for theorizing, I realized

that man differs from animals in that not only does he try to fit

into the environment, but he also tries to change this environment in

accordance with his own needs. In the material aspect man builds

canals, fertilizes the soil, plants forests. In the social aspect, he

tries to support the processes that he considers right and proper. At

some stage I thought that the social environment in the USSR could be

made more just, and that my activity in the Komsomol was helpful.

Later I encountered an unfair ban for Jews to leave the USSR and

tried to oppose this injustice. Among my friends there are very good

people who never and in no way tried to affect the social environment

and were calmly waiting for other people to change it, but it didn't

work for me.

We

Will Never Leave the USSR

In

December 1963 I graduated from the LITMO and, like all the graduates

in my specialty, I was sent to a military industrial complex, where I

worked for eight years. It was a large scientific-industrial complex

which included a research institute and a design office for

developing large and complicated electromechanical outfits for atomic

submarines, and also an experimental plant for producing the first

samples of these outfits. I started work at the plant, at the section

of adjustment, regulation and launching of these outfits. In the

beginning the work interested me very much, but with gaining

experience it turned into routine. In 1967 the institute opened

research in a new direction, and its goal was seeking methods of

evaluating the influence of the precision of the sets that the

complex was developing on reaching the final military aims and

comparing it with the anticipated expenses. The combination of

knowledge in engineering and mathematics made me a valuable worker

for the new field, and I was transferred from the plant to the

institute, notwithstanding the personnel department's objections

like "don't make it a synagogue".

Wedding. Leningrad, 25/01/1966

|

I

knew many girls - in the Institute, through hiking and later at

work. I never tried to get acquainted with a girl I met by chance in

the street or in transport. It happened for the first and last time

on October 12, 1965 in a bus. The girl's name was Anya Zusman. As

it turned out later, she also had never agreed to make a chance

acquaintance with a young man. Fortunately, she made an exception for

me. Two and a half months later, on January 25, 1965 we got married.

On December 14, 1967 our son Boris was born, and on March 1, 1975 -

our daughter Masha. In 1969 Anya graduated from Leningrad

Construction Engineering Institute (LISI) and was sent to work for an

organization that designed plants for processing wood.

In

1971 I got a Ph.D. for my thesis "Methods of Evaluation of the

Influence of the Systems under Development by the Institute on

Achieving Final Military Targets of Atomic Submarines". I detested

the final military targets and decided to leave military industry for

civil industry. Again, I had luck. I chanced to get acquainted with

the manager of the All-Union Institute of Jewelry Production. This

institute was developing new alloys, methods of growing synthetic

gems and new technologies for producing jewelry. The institute also

studied problems of economy, such as price formation and planning.

Irregular abrupt raising of prices for goldware and lack of

correlation between the assortment of articles and the demand of the

population resulted in overstocking of products. To overcome these

problems the Ministry of Instrument Making, which was in charge of

jewelry production, demanded from the institute to found a laboratory

for studying demand. This was a totally new field, and for organizing

a laboratory like that they needed a man with a wide scope of

knowledge and quite some cheek. I wanted to leave military industry

so much that I agreed to take a risk. There were no other candidates,

and the need for such a laboratory was so great that the ministry

agreed to appoint a Jew. The ministry obliged a powerful computing

center in Moscow to do all the necessary calculations for us. During

the years of my work there not only did I greatly improve my

understanding of economics, but I also acquired practical skills in

using computers.

Already

in my last years in LITMO I lost hope for an acceptable for me level

of personal freedom in the USSR. The reaction of most of my

co-workers to the intrusion of the Soviet troops into Czechoslovakia

convinced me that they did not need this freedom. I knew that Jews in

the USSR, along with all the numerous limitations, had one advantage

- a chance of leaving for Israel of another country of the free

world. For myself I saw this decision as unacceptable for a number of

reasons. First of all, my experience of learning German at school and

the institute and for passing the graduate school foreign language

exam showed that I would never be able to learn a new language.

Secondly, I thought that the situation in the USSR was tolerable for

Anya and me and that diligence at school and work would let our

children achieve life conditions they would find acceptable. Thirdly,

those who were leaving the USSR were obliged [in

the 70-ies - translator's note] to

pay for their higher education, and with three academic degrees and

one Ph. D. the sum we were supposed to pay was absolutely unreal.

The

Constitution of 1977 - the Turn to the Total Breakdown of Economy

in the USSR

The

media in the USSR were talking about great achievements of the Soviet

system, but their news was not connected to reality. I never paid

attention to it, so I saw the information of adopting a new

constitution in 1977 as another propaganda campaign. This was a

mistake. I gradually started to notice the re-distribution of power

in the country. The role of party organs in decision making in

industry had grown sharply. The party officials, as a rule, did not

have knowledge for managing production processes; their decisions

were motivated by politics, ideology and in many cases just personal

interests. The power of the enterprises managements and even

ministries was gradually moving to zero. I will give some examples.

The

Leningrad plant "Russkiye Samotsvety" ("Russian Gems") was

the largest producer of jewelry in the USSR. Its manager was a poor

production organizer, but he knew very well how to please party

bosses. For that, he organized a special department where the best

jewelers carried out individual orders of these bosses' wives. The

plant implemented production output plan by making wedding rings

without precious stones. Wedding rings production demanded less

labor, but lots more gold. In the end, the plant used up the entire

gold fund for three months ahead. The ministry demanded to dismiss

the manager, but the party bosses came to his rescue. They called the

CPSU Central Committee and complained that "the Ministry of

Instrument Making does not provide enough raw material for popular

consumption goods". As a result, the minister got a dressing-down,

while overspending of gold by the plant was going on.

Another

example. The ministry of Instrument Making received an order from

CPSU Central Committee for manufacturing pocket gold watches for

members of the Politburo. The instructions specified that the

watchcase should be entirely made of fine gold. At the conference on

this order, the representative of jewelry production noted that the

spring for opening the cover of the case could only be made of steel,

possibly with a thick gold coating. The answer of the minister was to

the effect that decisions of the party were to be carried out and not

discussed. The jewelry plant received an assignment to develop a fine

gold alloy with springy properties, even though it was clear to

everyone from the beginning that a thing like this could not exist.

Every

night at wholesale fairs of jewelry we calculated different economic

indicators for the assortment of concluded contracts and separately,

for potential orders of the trade. The administration of the ministry

often demanded to present these calculations at conferences with the

managements of the trade and representatives of the state planning

body, Gosplan, that were held at those fairs. In these cases I had to

be present in the conference room, to answer questions on the

calculations that could arise. These conferences dealt with issues of

economy. It continued up to the year 1978. In 1978 the participants

of these conferences already refused to discuss certain questions,

pleading lack of authority. In 1979 these conferences turned into

empty babble on unimportant questions. I remember one of the

participants saying bitterly after the end of one the conferences:

"Never did priests govern Russia. Not to them did the czar go in

times of trouble, but waited for the people's petition".

|